“I THINK POLITICAL violence leaves scars, like a national PTSD,” the Argentine journalist and fiction writer Mariana Enriquez said in a 2018 interview with LitHub. “The scale of the cruelty in political violence,” she continued, “always seems like the blackest magic to me. Like they have to satisfy some ravenous and ancient god that demands not only bodies but needs to be fed their suffering as well.”

Enriquez’s 2019 debut novel literalizes this black magic metaphor: the villain is a religious cult composed of wealthy, powerful members who worship a dark power they summon from another realm, their rituals rife with human sacrifice, torture, starvation, and rape.

Our Share of Night, released in English this February, primarily takes place in Argentina in the ’80s and ’90s, in the aftermath of the Dirty War, during which a US-backed military dictatorship killed and disappeared untold tens of thousands of people in brutal and gruesome ways. The full body count is still unknown, though the generally stated number is at least 30,000. This history obliquely provides the backdrop to the novel’s fantasy plot and also functions as a smokescreen: the Order’s sacrifice of innocents goes presumably unnoticed in the wake of mass slaughter by the military junta.

The novel opens on Juan, an emotionally turbulent man with a terminal heart condition who, since youth, has served as a medium for this cult. Juan occupies a position somewhere between slave and priest. He is the Order’s most powerful channel for accessing a powerful “Darkness” from which its members have amassed influence and wealth. Juan has a young son, Gaspar. His wife, Rosario, recently died in a supposed car accident, but the question of whether the accident was really a targeted attack kicks off the book. During the ensuing road trip out of Buenos Aires, Enriquez paints in quick strokes a landscape caked with dust and distrust, populated with flowers named from legends about dead girls and shrines for tragic figures like San Güesito, an impoverished young boy killed, gang-raped, and mutilated, whose grave was “covered with all the toys he hadn’t had in life.”

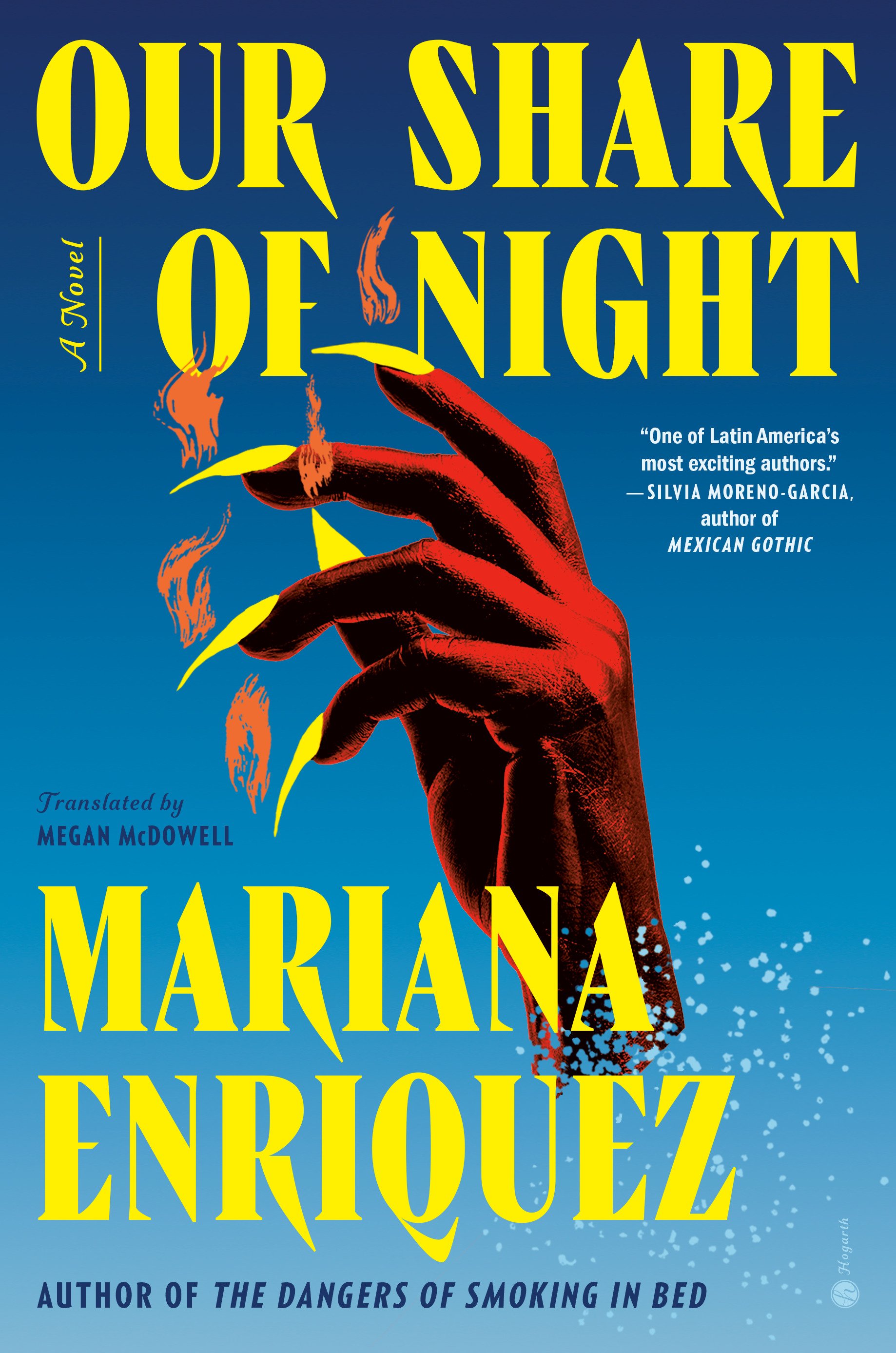

At first, the gritty realism and folklore-inflected horror feels like familiar territory for Enriquez, who has had two short story collections published in English: Things We Lost in the Fire and The Dangers of Smoking in Bed, which was longlisted for the Booker Prize. (Both collections, and the novel, were translated by Megan McDowell.) In these stories, ghosts of the disappeared run across bridges and girls punish social nonconformers by summoning spirits through Ouija boards. The narrative voice of Enriquez’s short fiction is taut, hard-bitten, and undeniably fresh. Her stories cross the boundaries between speculative, horror, and magical realist fiction with the ease of girls jumping fences, leading us somewhere more interesting.

In the short stories there is little room for the kind of obvious political allegory on which Our Share of Night is intent. The novel is hefty, complex, and ambitious, but some of the allegorical components—the devouring Darkness the Order summons, the cult’s naked greed and caricatured goal of eternal life—felt flat, overly symbolic. Throughout, the reader is fed parables of race, class, and colonialism. In an anecdote about the origins of the Order, a landed English gentleman with an interest in the occult travels to Africa, witnesses a local ritual with a native priestess, and takes her back to England with him as a medium, where she is forced to summon “the Darkness” until she dies. The narrator of this anecdote, a wealthy heiress of the Order, tells us: “All fortunes are built on the suffering of others, and ours, though it has unique and astonishing characteristics, is no exception.” This could be the moral tagline for the novel.

Violence is the novel’s throughline—ceaseless, unrelenting, unnecessary, perpetrated by the wealthy onto the poor, by parents onto children, by gods onto devotees.

But aphorisms alone do not make a 600-page novel, and for that, we return to the plot, which is dense and at times baffling. We learn that Juan hates his life in the Order and wants to know if Gaspar has inherited his abilities. If so, he wants to save Gaspar from repeating his suffering. From there, the book branches into six wildly different sections spanning nearly forty years, including one long interlude voiced by Juan’s wife, Rosario, set during the LSD-fueled “occult explosion” in London in the ’70s, and another section written as an unpublished paper by an anthropologist covering the opening of a mass grave in Argentina filled with bodies of the disappeared. The multivocal but not omniscient construction of the novel means the reader is given several limited perspectives and must read between the lines to piece together the rules for how the magic and fantasy in this world work, and what happened to major characters during large gaps in time.

This is no easy feat, as the exposition and worldbuilding can be elusive, even inconsistent. Consider these multiple explanations of the Darkness: “It was a panting sound . . . like dogs being choked by leashes.” “The silence was broken by the noise . . . which was marine and voracious, the smell of water.” “The Darkness is different when it’s unleashed inside . . . Enclosed, it bellows.” “I never did smell it. Some people smell decomposition; others, freshness.” “[A] boy spoke in the trance, pronouncing the words of the Darkness.” “That’s different now . . . the Darkness speaks, but not in the medium’s voice.”

The other fantastical devices—”Places of Power,” “Ceremonials,” an eerie realm called the “Other Place”—are similarly sketched out, with rules and landscapes that occasionally contradict and sometimes literally, physically shift.

The emotional heart of the novel lies in the fraught relationship between Juan and Gaspar. Our Share of Night follows the inheritance passed from father to son, which, read in one way, could be an allegory for intergenerational trauma. Juan wants to help his son escape the brutality of life under the Order, but can he ever truly? Juan’s motivation to protect his son is a form of fatherly love, but he doesn’t outrun his environment. In Gaspar’s narration, we find that Juan is a stern father, cold, unforthcoming, emotionally manipulative, and physically abusive. Indeed, it is the novel’s children who often suffer most, such as one Eddie: starved, tortured, and drugged by his mother, a member of the Order who wanted her son to gain medium abilities.

Unlike mass slaughter or human sacrifice, complicated family relationships resist easy moralization. Are we to excuse Juan for his violence towards Gaspar, done as it was in the name of protection, not greed? Was Juan’s brutality necessary to protect Gaspar, or was there another way? What about Gaspar’s own temper, his own violent streak, and the revenge he seeks as an adult? After hundreds of pages of description of arms stuffed into lungs and fathers slamming sons into broken glass, the writer’s final judgment on what to make of all this brutality is unclear.

Violence is the novel’s throughline—ceaseless, unrelenting, unnecessary, perpetrated by the wealthy onto the poor, by parents onto children, by gods onto devotees. In a rare moment of tenderness, Juan tells Gaspar, “I passed on something of me to you, and hopefully it isn’t cursed, I don’t know if I can leave you something that isn’t dirty, that isn’t dark, our share of night.” Perhaps there is no way to not pass along violence. Perhaps violence always begets violence. Perhaps senseless violence is just that: senseless.

While Gaspar never fully understands his tortured parent or the occult world he has inherited, he and his young friends do find a portal into something called the “Other Place,” a fascinating, horrible realm where bodies don’t decay and bones are arranged on trees, where the air smells like “old meat and sun-warmed crypt” and breathes like “a filthy mouth.” It is the source of the Order’s power and the magic, the source of the appetite for violence which demands, endlessly, to be fed. And it is, finally, in this brutal landscape that Gaspar, “felt some pity, in spite of everything.”