MISS MAJOR IS an icon of Black trans womanhood. Born in Chicago in 1946, she was on a path to some sort of Black middle-class life. At college in Minnesota, she left during her first term after a roommate discovered her femme wardrobe, came back to Hyde Park to live with her parents, and was arrested at twenty for speeding as she fled Chicago for New York. She did six months in jail for stealing the car.

Back when she was living in Chicago, her parents had taken her to see the Jewel Box Review, a drag show billed as “twenty-five men and one girl.” In New York, she reconnected with Jewel Box and worked in the show, supplementing that income with sex work and some other less-than-legal pursuits. The impossibility of living as a Black trans woman set her on a path into the prison industrial complex.

One strand of her story is that of looking for help—looking for allies—and realizing that trans people of color have to support each other and establish their own organizations. She offers salty assessments of many along the way; she describes Harry Benjamin, often credited as the “father” of trans medicine in the United States, as an “axe murderer” and “a very self-righteous old man.”

She found no place for herself in the Mattachine Society, a pre-Stonewall “homophile” organization. Her assessment of it is similar to her views on much of contemporary mainstream gay and lesbian politics, which offer no challenge to cis-het gender norms: “Why would someone want to assimilate into being something that was so hateful?”

Miss Major was arrested during the Stonewall rebellion in June 1969. “All I know is that night, they came in, and nobody budged.” For once, queer and trans people resisted the cops. “People want to know the little details, but what I remember most is being scared as hell.” Pride celebrations leave her cold. Mainstream, white gay and lesbian organizations erase and marginalize transsexuality, particularly trans people of color, for whom “it’s as if Stonewall never happened because it didn’t change anything for us.”

Influential strands of second-wave feminism—which define womanhood, much as patriarchy does, as an anatomical category—likewise had no place for Miss Major and who she calls “the gurls”—trans women of color. In her experience, it was the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, which policed entry according to body morphology, that “started the exodus of us from the women’s movement.”

Her most provocative language is reserved for the white gay men whose money and influence dominate gay political organizing, and who “have the nerve to feel that they’re on top and queens are beneath them,” who will put pictures of the gurls on their website but not on the board of directors. As for the Biden administration’s “listening circle” on queer issues, she says, “On the iPad it was like a sea of forty-seven white faces. I almost went blind.”

Gender politics that centers the gurls would not be about marriage equality or employment discrimination but would start with the police and mass incarceration. Miss Major says, “The prison industrial complex is like an octopus. . . . We have no idea where some of those tentacles are at any moment.” It reaches into schools, hospitals, social services.

One of Miss Major’s mentors was the prison abolitionist Frank “Big Black” Smith, a leader of the rebellion at the Attica prison in 1971. What she learned from him is that “you can’t throw anybody under the bus,” that you have to “see that everybody, everybody has suffered. That one is luckier than the other—it doesn’t do anyone any good to think like that. . . . We all struggle.” Miss Major also learned the dangers of being a token. “When the Powers That Be have tokenized us—giving attention to one of the group by making them feel that ‘Well you are different, you are special’—they usually do that in order to turn the rest of us against that person. That way they keep us separate.”

As an organizer, Miss Major tries to create spaces that the gurls can make their own. “In all the places I’ve worked I’m trying to make them feel as though its home, even if they’re just staying the night, or a few hours.” Such spaces have to offer not just safety and services but also the possibility of agency. “The trick is to build something that’s not just in the service of someone else, but is built by someone for themselves, and for everyone else that might also be in need. People have to self-organize their own places of safety, places where they can experience some freedom.”

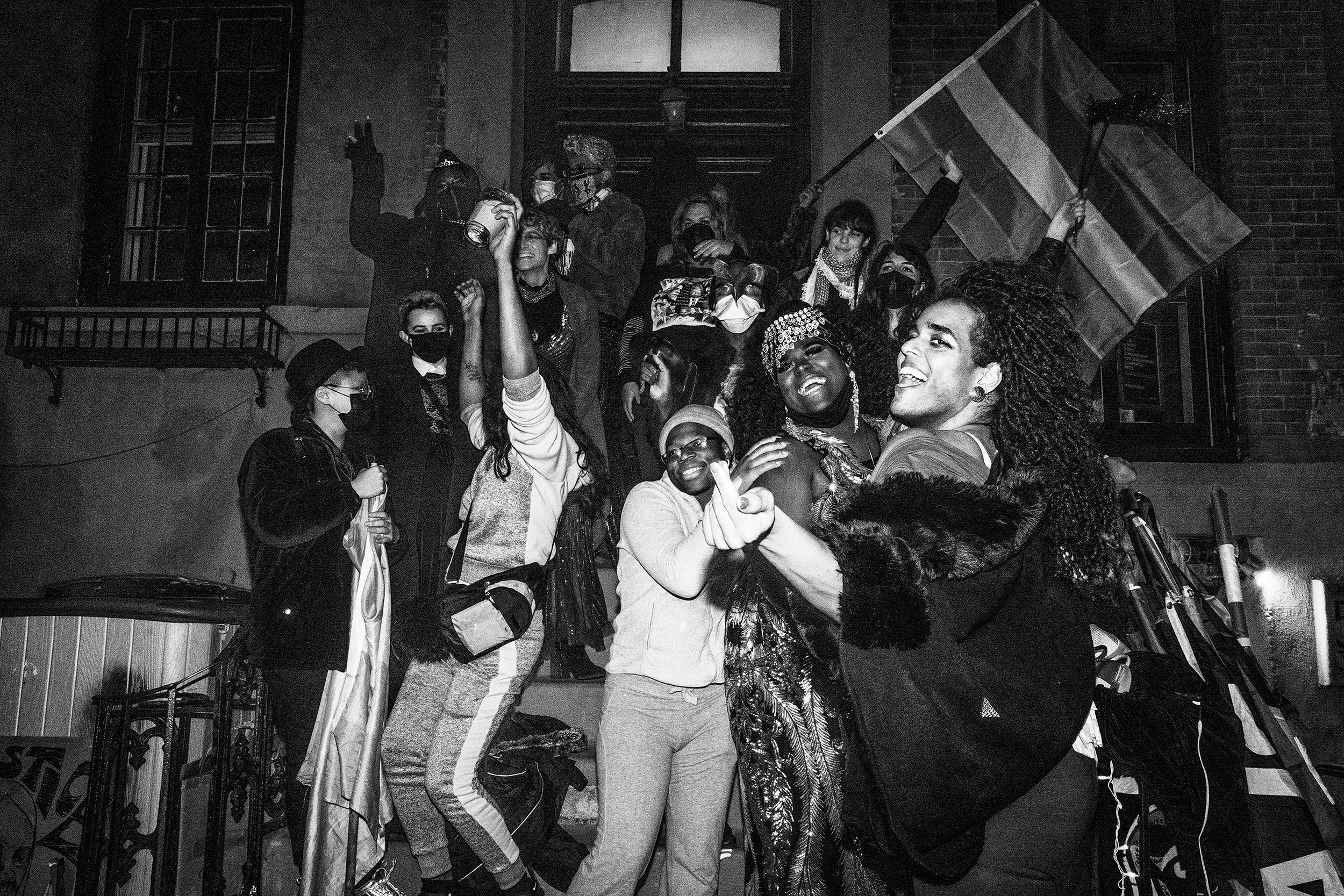

MISS MAJOR’S WORK continues and has been taken up by a younger generation of Black trans organizers. In the summer of 2020, Qween Jean, Joela Rivera, and others led a movement of street demonstrations in New York incited by the exclusion of Black trans experiences from white gay politics, but also from the Black Lives Matter movement. The photo book Revolution Is Love documents a year of street-based activity which centered the issues of trans women of color, starting with policing and mass incarceration but also including housing and food insecurity, mental health, suicide prevention, and the extraordinarily high incidence of violence and rape against the gurls.

Trans women of color are all too often expelled from their families and communities, left to fend for themselves on the streets, denied housing and legal work, snatched out of life into the prison-industrial complex, and abused and killed as if their lives had no value. If a movement for liberation, such as women’s liberation, is to be truly a universalizing and galvanizing movement, then it won’t be based on white, middle-class women’s experiences and priorities. It has to be based on joining the dots between the worst forms of oppression and the struggles against them.

The particularity of those experiences, in a kind of dialectical reversal, points toward a broad alliance of those who also struggle against some or all of those forms of oppression. The very existence of the gurls, so lovingly photographed in Revolution Is Love, is a call to abolish the conditions of existence that refuse to let them be—or, as Miss Major says, “They can kill us as a person, but they can’t kill the idea of who we are.”