BY PAGE 33 of her engrossing and candid memoir, filmmaker Joyce Chopra has revealed that while growing up in 1950s New York, men regularly exposed themselves to her in cruising cars, on the subway, and under the Coney Island boardwalk. She has been sexually assaulted by her brother and raped by an ex-boyfriend, has had an illegal abortion, and moved to Paris to pursue filmmaking, where she’s repeatedly ogled and groped by French producers; when she returns to the States, Al Capp, inventor of the comic strip L’il Abner, promises to help her meet the right people and instead thrusts his tongue into her mouth. Chopra is, by this point in the narrative, twenty-five; Harvey Weinstein is still in her future.

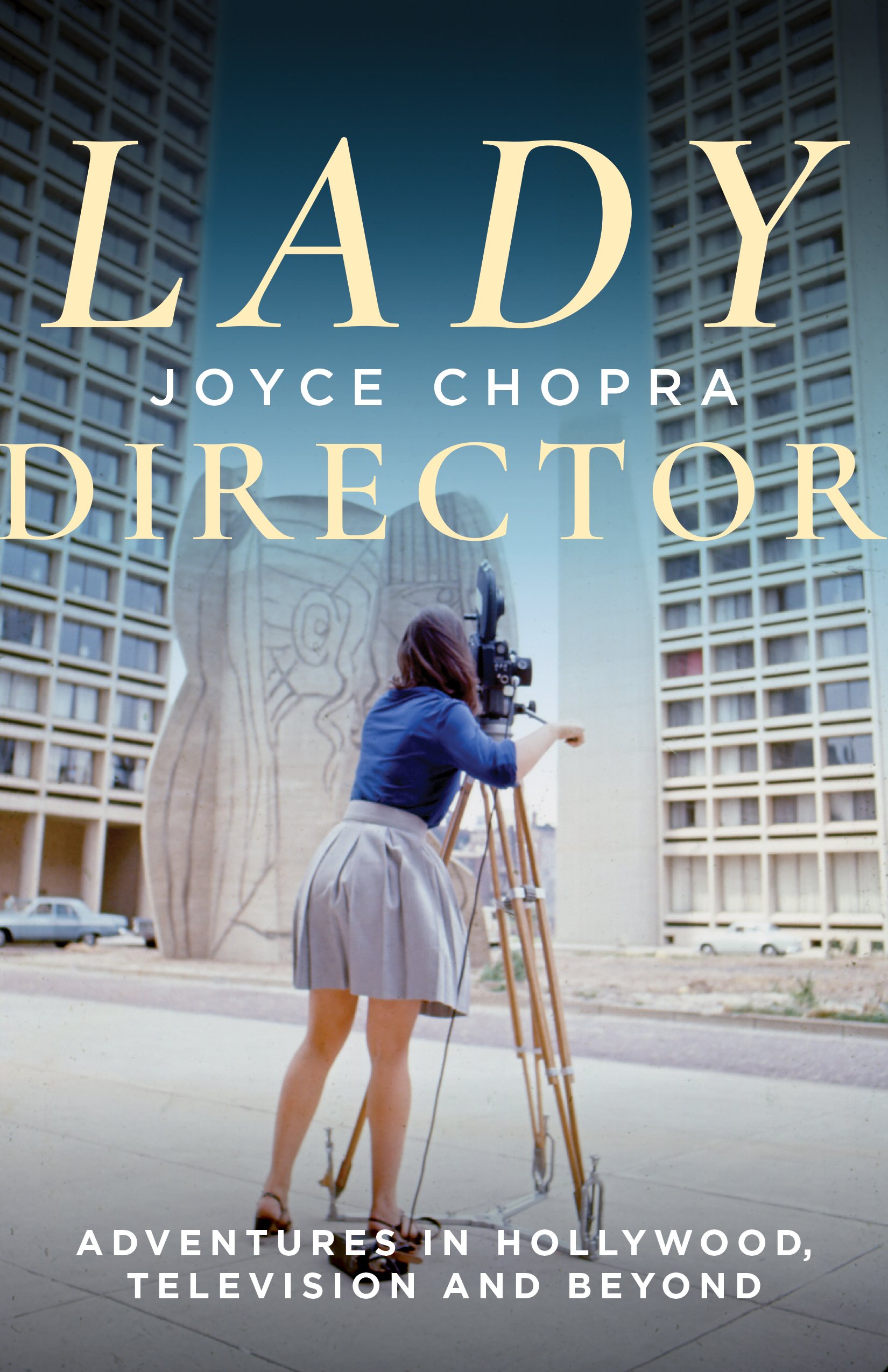

These harrowing encounters are a backdrop to Chopra’s larger tale of attempting to become a film director from age nineteen. As her life story progresses, she makes inroads into the world of documentaries, Hollywood films, and television movies, encountering sexist abuse at each turn. While there is material to justify its whimsical subtitle, Lady Director: Adventures in Hollywood, Television and Beyond is largely the story of a woman working under constant threat of sexual violence, intimidation, and aggression at the hands of terrible men. As she ages, the sexual harassment subsides, but even marriage to a collaborating screenwriter doesn’t temper the sexist workplace harassment she suffers at the hands of male producers and cinematographers.

As Chopra’s tale unfolds, we learn that after several attempts to make both documentaries and feature films—each thwarted by a man’s interference—Chopra lands on the idea that will lead to her seminal documentary, Joyce at 34. In 1972, documentaries were about famous people and notable events, not real life. Inspired by the launch of Ms. magazine (with Wonder Woman on its cover) and the success of Our Bodies, Ourselves, Chopra thinks the time is right for an autobiographical film about the realities of balancing motherhood, marriage, and a career. Her groundbreaking short doc is broadcast on PBS and marks the first live birth ever seen on television; Joyce at 34 was a sensation then and is now part of MoMA’s permanent film collection. Given the positive critical reception of her film, Chopra gushes to her father that women are now on the verge of making gains in every field. “It will never happen,” her father says. “Men will never give up their power.” Fateful words.

In the mid-eighties, after making several more documentaries and filming her husband’s play for American Playhouse, Chopra gets a chance to fulfill her longtime dream of directing a feature film. She and her husband adapt a Joyce Carol Oates short story, “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been,” and Chopra casts a teenage Laura Dern in the lead role. The film, Smooth Talk, wins the 1986 Grand Jury Prize for Best Dramatic Feature at the three-year-old Sundance Film Festival; Joyce Carol Oates praises the adaptation of her story in a New York Times essay. Chopra, nearly fifty, has arrived, and everyone who is anyone in Hollywood wants to work with her. She chooses James L. Brooks, the triple threat behind Terms of Endearment and The Simpsons, but that relationship sours when he doesn’t like the romantic-comedy script that she and her husband have cowritten. Still riding the wave of her debut film’s success, Chopra gets the plum job of directing the adaptation of Jay McInerney’s best-selling novel, Bright Lights, Big City, working with Sydney Pollack as producer. This is a pivotal moment in Chopra’s narrative and perhaps a pivotal moment in the story of American women directors; much is made of her being one of the first women hired to direct a big Hollywood film, so when Chopra is soon fired—due, in her estimation, to a clash with Pollack’s ego—much is also made of that. Producers go out of their way to discredit her as “in over her head” and “bad with actors,” and the press gobbles it up. A scathing takedown by New York Times critic Caryn James blames Chopra for relying too much on her husband and her cameraman. “It was all laughably untrue, but it was swallowed whole by every studio in town,” Chopra writes, “because it so easily fit into the narrative that women were a nasty bunch and never could be trusted to helm a big budget film.”

One could easily make the leap that being a woman filmmaker is itself hazardous to your career.

Chopra laments early on that she wasn’t aware of any women film directors when she set out to become one, but even if she had known, she says she would’ve been dismayed that their success didn’t last. This seems to be the motif in her own career: she simply could not leverage her early success.

This phenomenon isn’t just true of Chopra—in its inaugural year, Sundance’s Grand Jury Prize went to a woman director, Marisa Silver, who made just three more films before becoming discouraged and switching to fiction writing. Three years after Chopra won the top prize at Sundance, another woman director, Nancy Savoca, won that prize. She managed to make two more features before her career also veered toward television, with nearly a decade going by before she made another feature. Yet, in 1985, between those three women directors’ wins at Sundance, the brothers Joel and Ethan Coen won the top prize for their first feature, Blood Simple. The Coen brothers have codirected nineteen feature films and worked steadily for nearly four decades. One could easily make the leap that being a woman filmmaker is itself hazardous to your career.

CHOPRA HAS SURVIVED, making a career that has included years of directing made-for-TV movies and episodic TV, all while absorbing men’s wrath. As she says about being hired to direct Law & Order: SVU in 2002, “. . . the price of entry was verbal abuse from a producer who didn’t want any females around.” As for Harvey Weinstein, Chopra feels compelled to note that he didn’t sexually assault her, but he clearly bullied her. Chopra directed a film starring Diane Keaton, The Lemon Sisters, that Miramax financed. Weinstein hovered over her menacingly in the editing room (“his large body jammed beside me”) and humiliated her in front of colleagues. During a meeting about the film’s opening titles, he said, “Go away, Joyce. No one wants you here.”

To be clear, Lady Director is fascinating beyond Chopra’s struggles with intimidating men. In fact, many of her “adventures” are a cultural historian’s dream. For instance, when she’s fresh out of college, Chopra and a classmate open a music club in Cambridge, Club 47, where they hire a newcomer, Joan Baez, to perform regularly, singing duets with an as-yet-unknown Bob Dylan. When, in 1960, Chopra randomly lands a job as an editing assistant for an early-career D. A. Pennebaker, she finds herself capturing footage of President John F. Kennedy’s inauguration. When she sells her half of the music club to her partner and moves to Paris, intent on pursuing her filmmaking dream, she gets to see Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless upon its release in the city where it was made. When she makes her autobiographical short doc, both Shirley MacLaine and Gloria Steinem endorse the film. When she visits Nigeria to make a Ford Foundation-funded film about the work of pediatrician Olikoye Ransome-Kuti, brother of the famous Afrobeat and protest musician Fela Kuti, she sees Fela perform at a pivotal juncture: shortly after soldiers have thrown Fela’s mother from a window and she has died from the injuries. When Chopra takes Smooth Talk to Sundance, the festival is so young that “Bob” [Redford] watches all the films and hangs out with festivalgoers. It’s exhilarating to travel alongside her as so many well-known figures cross her path; in every phase of her adult life, Joyce Chopra has been there, in the thick of things, at the center of key movements and moments.

Because her filmmaking life spans more than five decades, from the 1960s to the 2010s, Chopra’s memoir narrates a revolution in women’s lives (and, as an aside, a technological revolution in the tools of filmmaking). Lady Director is the story of one woman’s life, for sure, but it’s also a story bookended by the women’s liberation movement and the #MeToo movement and the patriarchal resistance and backlash that has stubbornly remained throughout. This memoir is also a chronicle of how one woman of Chopra’s generation grapples with wanting to be a fully present mother but also continue working in a demanding field. This ongoing tug-of-war is illustrated best when she finds herself unexpectantly pregnant at forty-four and chooses to have an abortion. It should be a relief to read that after her illegal, secret abortion experienced alone when she was in college, Chopra is able to have a legal, safe abortion two decades later as a married woman, but Roe’s demise has turned this into a sad tale of regression. Now there are also draconian outcomes for doctors performing abortions, anyone who helps a woman terminate her pregnancy, and pregnant women themselves who seek the procedures to save their own lives. It’s sobering.

Lady Director can leave you with the feeling that at every turn, if she’d been given the benefit of the doubt—as so many male directors have—Chopra could’ve had the career she always yearned for and become a more-widely known film director, yet she’s never stopped working. Even in her early eighties, Chopra is still producing fascinating, socially conscious documentaries. As a result of her lifetime commitment, she has a body of impressive work and has paved the way for a generation or two of women directors who came after her. (As is apropos, The Criterion Channel is featuring a retrospective of her films to coincide with the publication of this book.)

Chopra opens this memoir by saying she wrote it to answer a question she gets from so many young women: How did she do it? How did she manage to have that career, despite the hostility she faced? The book’s final chapter reports abysmal statistics alongside encouraging ones about women directors in Hollywood, and yet offers no real answer to that fundamental question. In a postscript, she says that she first resisted writing a memoir, but then she typed a few sentences and just kept going.

“And maybe that’s the point of all this,” she writes. “Just keep going.”