I’VE PREFACED FAR too many conversations lately with “I’ve just read Kafka’s diaries.” I actually read Kafka’s diaries about six months ago, but I can’t shake the feeling I’ve discovered something incredible. It’s silly, I know. Surprise, surprise: Kafka is good. But I’ve been acting like a teenager in love with a pop star. Recently, a Berliner boy I was on a date with informed me that his father was a distant relative of Kafka’s mother. “Are you serious?” I answered, fawning, clasping my hands to my mouth. “No fucking way!”

On Kafka’s staying power, Los Angeles Times book critic David L. Ulin writes, “We are all of us conflicted, all of us trapped in situations we can’t escape. . . . And Kafka remains our greatest chronicler of this ambivalence precisely because he understood it . . .” It’s because of that understanding that so many readers throughout the years have felt that Kafka understood them specifically, myself included. Much of his work remained unpublished in his lifetime, which perhaps allowed him to write so openly about a specific type of suffering: pain caused by the knowledge of pain itself. Kafka knew he could never escape his own anguish, and that was why he wrote.

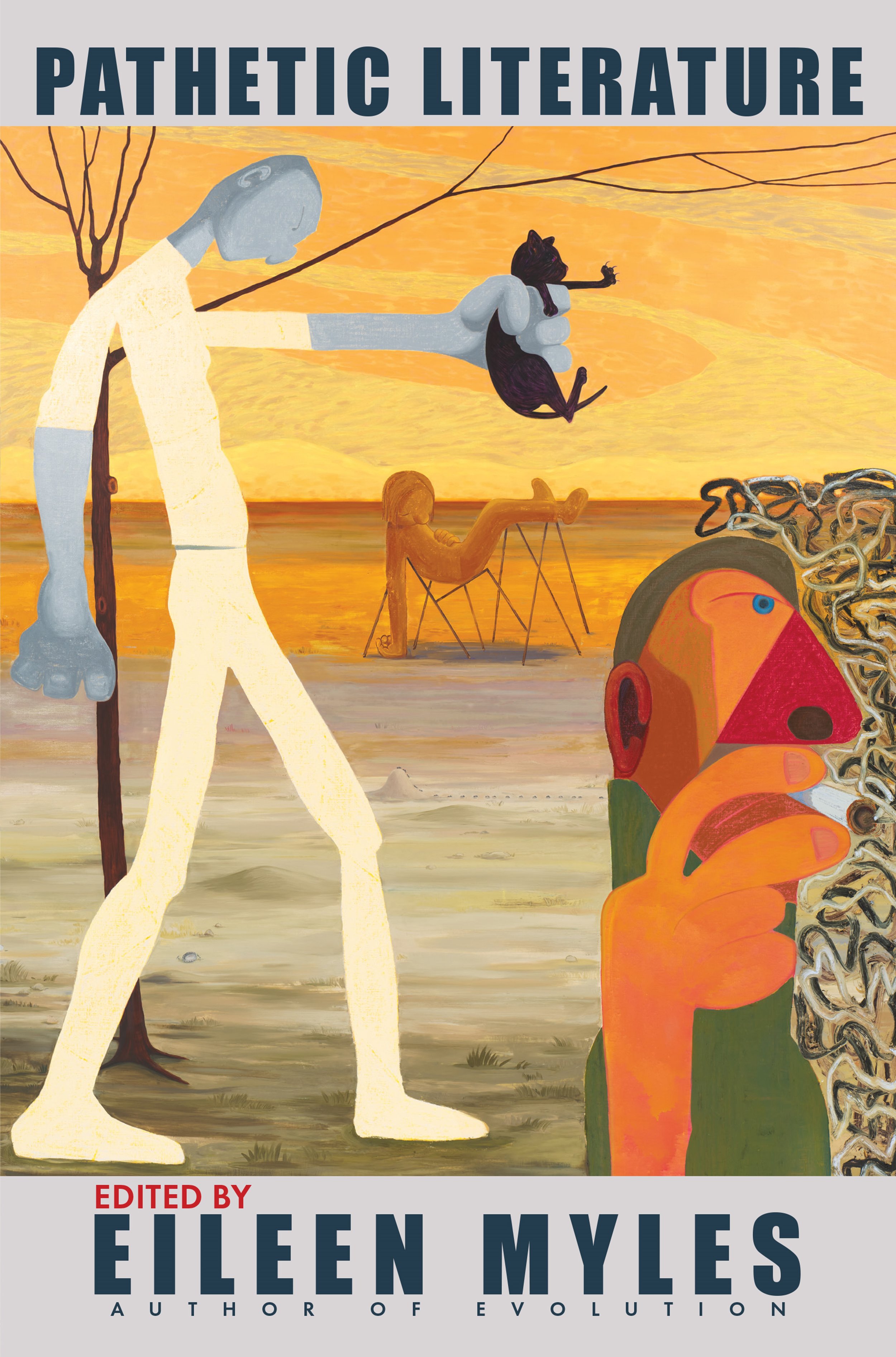

Eileen Myles knows it, too, and that’s why they stuck a letter of Kafka’s into an anthology titled Pathetic Literature. I appreciate the book’s lack of a subtitle; it is what it is. Myles starts the introduction bluntly: “In general, poems are pathetic and diaries are pathetic. Really, literature is pathetic. Ask anyone who doesn’t care about literature. They would agree. If they bothered at all.”

Pathetic, as we are to understand it in this context, has something to do with acknowledgment (and bold articulation) of feelings that—because they are embarrassing, because they make us vulnerable or worthy of pity—are often left unexpressed. Myles is not so straightforward in telling us the word’s precise connotation. They go on to admit that the works included in the anthology are more or less just ones they love. (Love, as argued below, is pathetic.) Rather than dampening the experience, this lack of a definition encourages me to read more intensely, to search for meaning, to jot down notes as I go along. I end up devising several categories of pathetic-ness: Self-Hatred, Grief, Prejudice, Queerness, Love, and Desire. Spanning these topics, Myles places works by Rumi and Borges alongside those by Dennis Cooper and Valerie Solanas. If we assume that the act of writing literature—of acknowledging and cataloguing the deepest caverns of human emotion—is pathetic, ergo embarrassing and all too self-revelatory, then there’s no reason not to place the classics on the same level as modern ramblings. Honestly, isn’t the whole idea of literature a bit ridiculous in the first place?

Self-Hatred seems to come up the most, and of course, that’s where Kafka lands.

More about my categories. Self-Hatred seems to come up the most, and of course, that’s where Kafka lands. In a letter to his judgmental father (the villain, as he saw it, of his own life and work), Kafka describes himself as “mentally incapable of marrying” due to a cocktail of parental disapproval, a tendency to idolize his lovers, and general inadequacy. Indeed, no one has ever hated Kafka more than he hated himself; in his diary, he writes, “People label themselves with all sorts of adjectives. I can only pronounce myself as ‘nauseatingly miserable beyond repair.’” Likewise, in an excerpt of her novel Great Expectations, Kathy Acker writes, “Everyone hates me. My mother may have been murdered. Men want to rape me. My body’s always sick.” These writers and characters are pathetic because they say they are. Toward the end of a poem called “It’s dissociation season,” poet-artist Precious Okoyomon admits, “I’m no good at taking care of myself”—a through line of the anthology.

Grief, on the other hand, is the result of external circumstances, rather than the writers’ feelings about themselves. Still, grief is embarrassing, as these examples show: Samuel Beckett shitting in his dead mother’s toilet to feel close to her; Michael McClure going mad over the deaths of a hundred whales at the hands of US GIs. Prejudice is addressed, similarly, as a pain so deep that anyone, no matter how strong, becomes pathetic under its weight. In Baha’ Ebdeir’s “A Description of the Camp,” the speaker is literally objectified, writing in the perspective of the wall which imprisons Palestinians: “My mother calls me the apartheid wall, but my stepmother calls me the separation wall. I am a wall that dehumanizes the humans living in the camp.” Lucille Clifton walks along the edge of another oppressive structure in the poem “slave cabin, sotterly plantation, Maryland, 1989.” She writes:

when she aunt nanny sat

feet dead against the dirty floor

humming for herself humming

her own sweet human name

Myles has selected writing on political oppression from a wide, multinational variety of queer writers of color; the misery of queerness is also a recurring theme throughout. Myles touches on this in their afterword: “In a despotic or theocratic culture, trans people are always pathetic, but I think at least in America, where I sit, we have passed out of the most overt abject of that phase (not because Joe Biden won but because Donald Trump didn’t).” It’s a bold claim to make, especially as new elections approach and more discriminatory bills are passed, but Myles acknowledges a persistent reality in which queer people are ashamed and afraid and alone. Valerie Solanas’s 1965 play Up Your Ass makes a brief appearance and, in a conversation about eliminating males as a sex, a character comes upon a radical conclusion:

RUSSELL: No! The two-sex system must be right; it’s survived hundreds of

thousands of years.

BONGI: So has disease.

Love, too, is pathetic because it hurts us in a way we can’t control. “I’d like to pick up the phone sometimes and just find that you are there,” Camille Roy’s father confesses in “Reading My Catastrophe.” Aren’t such admissions painful? Don’t they make us feel frightened and small? Myles ends the anthology on such a note; its final piece is a poem by Will Farris called “Orlando,” which concludes, sheepishly, “I feel like smiling somedays / it can’t be helped.” Desire is pathetic, the horrific and wonderful indignity of sex-having and -wanting. As Judy Grahn writes in “A Woman Is Talking to Death,” “I am a pervert, therefore I’ve learned / to keep my hands to myself in public.”

Maybe the way these pieces relate to each other seems opaque, but I am 672 pages inside Eileen Myles’s head, and it all makes perfect sense to me. Spending time on this book gave me the same feeling that reading Kafka gives me, the same feeling that I’ve been going through the world with after reading nothing but Dennis Cooper for a month or so. I grin to myself—really grin—when I come across both names in Pathetic Literature, feeling like I’ve discovered something incredible, like Myles knows me. A Berliner girl I’m on a date with asks what books I’ve read lately, and I tell her Cooper’s George Miles Cycle, and then I say, “I can’t in good conscience recommend it to you,” because it’s embarrassing. All too self-revelatory.

I would recommend Pathetic Literature. It’s pessimistic, kinky, and mean. There’s lots of scat and descriptions of genitals. It might depress you, but probably only if you were depressed beforehand. What I know is that I’ll keep the book with me, just like I keep a German copy of Kafka’s diaries on my bedside. I bought it from das Kulturkaufhaus Dussman in Berlin because I convinced myself it was more profound than the English copy sitting on my nightstand on Long Island. Pathetic.