YOKO ONO SELF-PUBLISHED Grapefruit: A Book of Instructions and Drawings in Tokyo in 1964. In 1970, this visionary work of conceptual art was published in the US. Ono’s “instructions” were a radical approach to art because they centralized the participant in the work to manifest the piece, whether the artist was present or not. Some of the instructions read like Zen koans, many of them only to be realized in the reader’s mind. In Smoke Piece (1964), for example, “you” are directed to “Smoke everything you can. / Including your pubic hair.”

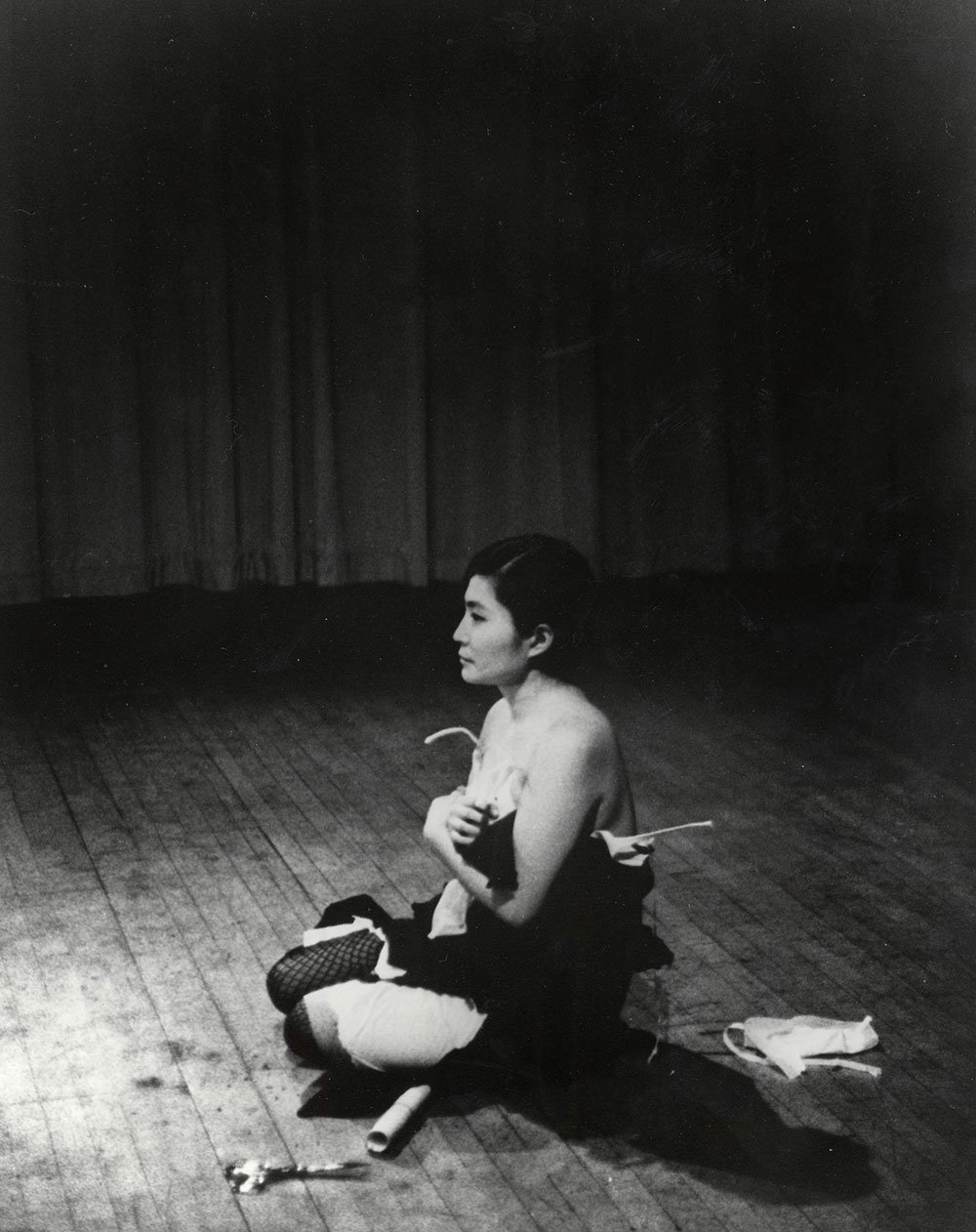

Grapefruit includes Cut Piece, a performance that predates the launch of the feminist art movement. The instruction reads: “Cut.” When Ono has performed the piece, she sits onstage with her legs folded beneath her in seiza, a traditional Japanese sitting position, wearing her best outfit. A large pair of fabric scissors rests before her. Members of the audience are invited to come onstage, one at a time, to cut a small piece of her clothing to take with them. Ono sits motionless and silent for the duration of the piece. Like many of her works, the piece transposes the performer-audience relationship, turning the audience member from passive voyeur to implicated agent. Audience participation, as well as the environment in which it is performed, are essential elements of the piece.

Her 1965 performance of the piece at Carnegie Recital Hall, New York, was filmed by the documentarians Albert and David Maysles and included in a 2015 survey of Ono’s work at the Museum of Modern Art. The film depicts a man holding the scissors while circling Ono; another comes onto the stage twice, the first time to cut a piece of her clothing in front of her breast, the second time to shear off her blouse. He then cuts off both of her bra straps, causing her to hold up the bottom of her bra for the remainder of the performance. He addresses the audience directly while standing above her with the scissors in hand: “Very delicate, might take some time.” The sound comes in and out: jolts of laughter from the audience, shoes clomping loudly on the floor as participants move in and out of the frame. White figures fade into the oblivion of a dark shadow as they exit the stage after surveying and circling her, cutting off pieces of her clothing wherever they please. It feels simultaneously out of control and tightly orchestrated, and it is this tension that made me so nervous while watching it. Cut Piece brought me into myself but then instantly into the deeper, more fearful places inside of me that can only be activated by the specter, even whiff, of male violence. It makes me remember. It makes me scared again.

The work is visceral. It helped break the silence in which rape and sexual violence were shrouded at the dawn of the women’s liberation movement; it made visible the aggression perpetually directed toward the female body. It also made the participant complicit in the act of exploitation, in the once-hidden nectar of their abhorrent self.

When I watch the young white male in a stylish white shirt, dark business slacks, and slick shoes who’s come back a second time to cut away Ono’s bra, it brings me immediately back to my frequent sighting of the young white man at my undergraduate university who used to walk across campus to his classes in a dress shirt, carrying a leather briefcase, channeling Patrick Bateman in American Psycho. Like the actor who played Bateman in the movie, his name was Christian (I don’t remember his last name). I had heard stories about him threatening a woman in her dorm-room bed with a knife. Later, he beat and raped a friend of mine, yet despite her and our activism for the campus administration to hold him accountable for his crime and kick him out of the university, he remained. When he showed up in my summer environmental course and the professor asked if there was anything we wanted to share before we began our fieldwork, my heart leapt into my throat as I contemplated asking for Christian’s removal from the class.

I never spoke up, though. I could not shatter my own silence—or, perhaps, I chose to silence myself. Once, while parking at the outdoor site of our class, I pointed him out to some female classmates and said, “He raped my friend.” They made some kind of basic acknowledgement—“Oh” or “Oh, wow”—I can’t remember exactly. I do remember they asked me nothing and said nothing more. Christian disappeared into oblivion the way that man in the Cut Piece film disappears into the darkness after taking a short leap from the stage, leaving Ono holding up the bottom half of her bra and leaving me holding that ancient block of fear in my gut.

If Cut Piece is a feminist work, it is not one that is reducible to a single reading.

CUT PIECE DEPICTS a body in resistance to the tyranny of a self-actualized mob. Even though that body does not react in a way that fits expectations of resistance or even rage, Ono creates a way to implicate the mob (the audience) without the artist speaking a word or taking action. Cut Piece evokes for me the early feminist art movement, which created art from women’s testimonies about their lived experiences under patriarchy. By 1971, Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago had created the Feminist Art Program at CalArts and embarked on the famed group exhibition, Womanhouse, which featured performance art and installations. Many artists associated with this movement centered live female bodies in their work. Carolee Schneemann’s Interior Scroll, in which the artist reads a manifesto unfurled from her own vagina, is a frequently cited example. For the first time, women-identified artists began to create performance work about sexual violence. Suzanne Lacy staged the landmark Ablutions in 1972, in which recorded testimonies of sexual assault played while women enacted rituals onstage, such as bathing in a vat of eggs or nailing beef kidneys to the wall.

Many of these early feminist artists were influenced by the avant-garde circles in which Ono was an important but overlooked figure. Lacy studied under Allan Kaprow, who coined the term happenings to describe the perishable and performed art taking place in nascent movements like Fluxus, which Ono helped found. She and other Japanese artists, including Yayoi Kusama and Shigeko Kubota, helped change the course of art history by using performance to turn the female body from the subject to the locus. According to Midori Yoshimoto, art historian and author of Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York, they “reclaimed their bodies as active agents of artistic creation before the women’s liberation movement emerged. Their impact on women’s performance art, however, has generally been overlooked.” Early groundbreaking works like Kusama’s body-painting performances of the 1960s—in which she painted polka dots on nude performers at large gatherings in public places—or Kubota’s Vagina Painting performance—in which she simulated painting from her vagina by affixing a brush to her underwear, dipping it in red paint, and squatting while painting menses-like marks on white paper—made possible the later feminist works which focused on women’s bodily autonomy. On the eve of the women’s movement, Cut Piece centered the female body in performance art.

“Cut Piece was perhaps the earliest example of Yoko’s work with a clear feminist message about male objectification of the female body and societal pressure for women to remain passive,” Yoshimoto told me. The fact that Ono featured herself in the piece created, as Yoshimoto noted in Into Performance, “an enormous tension between her and the audience primarily because the audience was unexpectedly put in a position of committing themselves to a taboo behavior. Since the subject was a woman, the act of stripping her piece by piece resembled a rape.”

Ono traced the inspiration for Cut Piece to an allegorical tale about Prince Mahasattva, an incarnation of the Buddha, who leaves his castle with his wife and children to travel to a mountain and meditate. Along the way, he gives his wife, children, and clothing away to people who ask for them; finally, Ono recalled, “a tiger comes along and says he wants to eat him, and Buddha lets the tiger eat him, and in the moment the tiger eats him, it became enlightened.” The tale symbolized “total giving,” and Cut Piece was the artist’s exploration of a philosophical stance of radical resignation and how such a stance mediates life experiences. In her telling, the work was not explicitly about gender, race, or ethnicity. And yet, identity haunts the piece, which operates on multiple levels and can be interrogated through many lenses. To art theorists, it is a piece about the self versus the other; the private versus the public; victim versus assailant; alienation versus connection; subjectivity versus objectivity; and so on.

If Cut Piece is a feminist work, it is not one that is reducible to a single reading. It is political but also mystical. It is about being a woman, and it is also about being a Japanese woman, both in Japan and in postwar America. “Before the rise of the official feminist art movement around 1970, [Ono] understood a key dynamic in the relationship between the artist and the audience,” says Amelia Jones, a feminist curator, theorist, and historian of art and performance. “As a Japanese woman, performing this piece in Japan and then in New York, she set up a situation of great tension and made audience members aware of the violence of viewers towards objectified images of women and, in the New York case, Japanese women in particular.”

As Jones suggests, it is near impossible to separate Ono’s identity as Japanese and female from her performance of the work. Ono “put her body in your face, so to speak,” Yoshimoto says, and her performance of Cut Piece has enduring relevance for generations of artists, as it interrogates gender, sexism, racism, xenophobia, and the male gaze. As such, Ono created a piece that situates itself—and her body—in an intersectional framework decades before Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw identified the term to describe “the double bind of simultaneous racial and gender prejudice.”

ONO CONTINUED TO address the violent mob mentality and women’s exploitation in work created after Cut Piece. In 1966, on the occasion of The Stone, a collaborative art installation at the Judson Gallery in New York, in which Ono was the only female artist represented, she included a text piece titled Statement, which elaborated on her performance in Cut Piece. She wrote: “People went on cutting the parts they do not like of me finally there was only the stone remained of me that was in me but they were still not satisfied and wanted to know what it’s like in the stone.”

In 1969 and 1970, she directed two 16mm films—the seventy-seven-minute film Rape and the minute-long Freedom. Rape follows a Viennese woman (played by Eva Majlata), encountered first walking through a cemetery in London. After first being flattered by the attention of the two-man film crew, Majlata then rebuffs them in Italian, Hungarian, German, and lastly, in English. According to Alexandra Munroe and Jon Hendricks’s book YES Yoko Ono, “The film, shot mainly in close-up with a hand-held camera, eventually traps her in a room, where she behaves like a cornered animal, lashing out at the camera.” Freedom features, Ono, clad in a purple bra, pulling at it as if attempting to free her breasts. (Bras were an indelible symbol of the women’s liberation movement after the 1968 Miss America pageant protest, in which feminists threw their bras, heels, false eyelashes, girdles, and other “instruments of torture” into a “Freedom Trash Can.”) Soon after, in her essay “What Is the Relationship Between the World and the Artist?,” Ono wrote, “I like to fight the establishment by using methods that are so far removed from establishment-type thinking that the establishment doesn’t know how to fight back.”

Feminist discourses about gender and the body have evolved since Ono and other artists centralized their bodies in their work. Increased visibility of LGBTQ+ and gender-fluid concerns in the culture have led some art theorists to explore the limits of a feminist approach to identification and reconsider the relationship between essentialism and feminist visual theory. Cut Piece, and Ono herself, was at times overlooked, misunderstood, or in conflict with the early feminist art movement, which Jones says was dominated by white women of the second wave concerned with exploring women’s exclusion from art history and the tendency to downgrade female experience. Ono was often written off as the wife of a famous man, not an artist or movement builder. Judy Dlugacz, one of the founders of the lesbian feminist collective Olivia Records, recalls Ono reaching out in the early 1970s to collaborate on a project, which Olivia rejected. (“We were so stupid,” Dlugacz later commented.)

To many feminists of that era, the political dimensions of Ono’s work were not legible as such. When asked later to speak about Cut Piece through a feminist lens, Yoko focused on her agency in the piece: “The fact that I decided that people can take wherever they want to take, not wherever I want to give, was a very important thing, because that is my experience as a woman in life. . . . Because I was a woman, I didn’t think of it like a feminist act, I thought that was the real act because that was how life was for me.” When Ono created Cut Piece, she specified that the performer need not be a woman. She also created a second version of the piece, in which it would be “announced that members of the audience may cut each other’s clothing. The audience may cut as long as they want.”

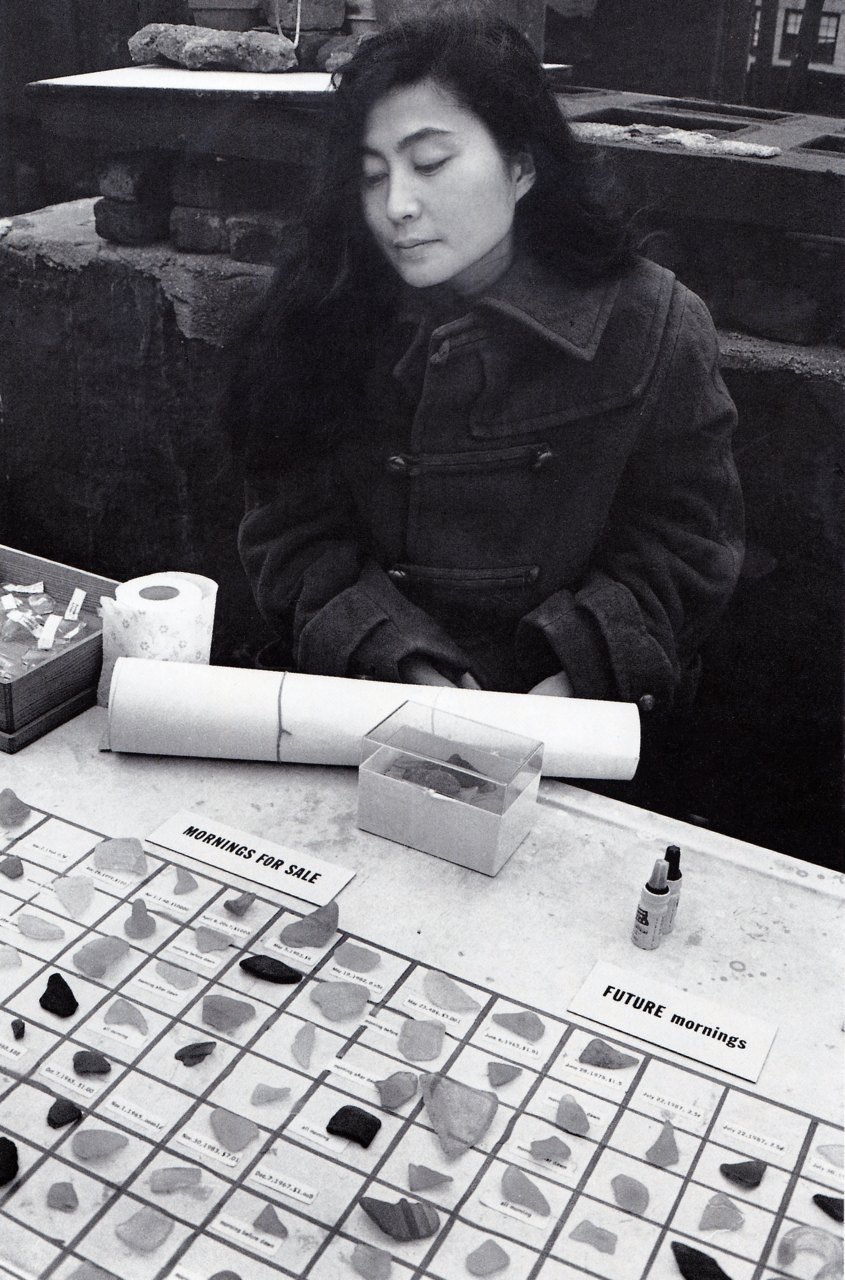

Ono performing Morning Piece on the rooftop of 87 Christopher Street, New York, 1965. Photo by Peter Moore.

IN THE EARLY nineties, when I first organized with other feminists to expose and fight against the prevalent rape culture on our campus, I used my words in consciousness-raising sessions, campus newspaper articles, and leaflets we distributed at rallies. I and my “sisters” in Gaia, our feminist activist group, did not employ a visual language or use the performance-art techniques that the Guerrilla Girls were harnessing then in nearby New York City to fight sexism in the art world. It wasn’t until I worked at Ms. magazine a few years later, and saw a black-and-white photo tacked up on the art-department wall of Kathleen Hanna in a bikini top with the word slut written in capital letters across her belly, that I felt the visceral power of feminist iconography. That image said more than my 1,500-word editorials had ever said—and it did it faster, indelibly. That image led me to Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (Your body is a battleground). It led me to Tracey Emin’s My Bed. Then it led me back—to Judy Chicago, Miriam Schapiro, Adrian Piper, Martha Rosler, Judith Bernstein, Hannah Wilke, Ana Mendieta, Carolee Schneemann, and Yoko Ono.

Something about Ono got rooted in me, but it was more philosophical than feminist. The more artwork of hers that I saw and participated in, the more it opened spaces inside of me that had been previously closed. Even though I was an outspoken feminist activist on campus, I could mainly do it behind the desktop with my words; I didn’t have to be seen. I didn’t have to show my face and my body. I felt better off inside of myself, churning through ideas and ways of being in small, discreet moments—and Ono’s work actually met me there.

More recently, I encountered a photograph of Ono in a dark coat sitting at a white table on the roof of her apartment building at 87 Christopher Street in September of 1965. She was performing Morning Piece. Signs printed “Mornings for Sale” and “Future mornings” announced rows of labeled sea-glass shards. Typed labels with a future date and time of morning—“March 3, 1991, until sunrise,” for example—were affixed to each shard. I considered the idea of selling mornings that once existed and were gone or had yet to exist and were not here. For a moment, I was suspended between the past and future, free.