Private collection, New York.

I DIDN’T KNOW a painting could make me feel as if I were falling. It happened for the first time when I saw an untitled 1948 painting by Louise Bourgeois in the current exhibit of her work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A vivisection of a seven-story apartment building, it suggests both an internal and external space in which creatures are climbing, flying, holding on for dear life, and possibly dying. Splotches of gray on the ground floor suggest a body has been removed; a vertical column of black hovering to one side may indicate a nun or a shadow or possibly an elongated spider with a few thready legs trailing out. Immediately to its left, stretching from the top floor to nearly the bottom, is the suggestion of a Rapunzel-like spray of hair—surely a self-reference for Bourgeois, whose hair was very long during this period. This chaos of unsorted symbols, which foretell so much of the art to come, is the internal space of someone who feels in need of rescue before she falls or flies apart or actually dies.

The intense red-orange of the background suggests a conflagration of rage that threatens not just one person but a whole building. Agoraphobic, acrophobic, depressed, self-reportedly often enraged and at times suicidal, Louise Bourgeois had a long gestation to become one of the twentieth century’s preeminent sculptors. First, she was a painter for roughly ten years following her emigration to the US from France in 1938—the Met’s is the first comprehensive exhibition of her work from this period. She was also a wife to an ambitious and successful art historian and curator, Robert Goldwater, whom she married in Paris after a courtship of a few weeks. Three sons—one adopted—arrived rapidly after her marriage and emigration.

It’s a lot for one life. It’s a lot for one image, but there is still more going on in this untitled 1948 painting: Up on the roof of the building, a figure holds some kind of tool with both hands. Beside her are lit birthday candles or fireworks or possibly pieces of sculpture. More will happen if she can just escape the confinement of the building, its perils, its heat. This was not just a fantasy, for—at least occasionally during this early part of her career—Louise Bourgeois was making sculptures on the roof of her apartment building, despite her fear of falling.

If sculpture was ultimately to become her chosen language, she still had plenty to say in two dimensions, as this exhibition of nearly fifty paintings makes clear. Her materials are often rough and roughly used: plywood scraps, thinly layered paint, a limited range of colors. Here we sense the frugal housewife who understood that art was taxing to the family, economically as well as emotionally. Beauty is not what interests her, nor verisimilitude, nor developing a style to compete with the boys. “Art is not about art,” Bourgeois said in a 1988 interview with Donald Kuspit. “Art is about life.” Since this exhibit makes little attempt to connect her early work to her later inexhaustible creativity, these words seem helpful. These paintings are about life—her life and possibly ours too.

Throughout this decade of work, we are witness to an artist struggling to emerge, held down by the very forces she seeks to express. Red Night (1945–47) depicts an actual birth of sorts with its mummy-like mommy lying in something between a hospital bed and a funeral bier. Two dear little faces pop out between her underarms; a third is emerging between her legs. The babies look happy enough, held if not cradled. The mother, one eye spiderlike, the other a dark hole, looks at once becalmed and etherized as she floats in a red sea, relieved only by a blue, cloudlike apparition, perhaps representing what remains of her life. Certainly, we can see Picasso’s glancing influence in the mother’s asymmetrical eyes and the economical strokes that compose the babies’ humorous faces. But the anguish, the disassociation, the terror portrayed is Bourgeois’s achievement. Those babies have made their mother into a patient and they seem to be having a pretty good time while they do so. Although their mother is in danger of dying, the children, while connected to her body, will thrive.

Private collection, New York.

BOURGEOIS LATER SAID many times that she would have never become a sculptor if she hadn’t come to New York. An early painting in this exhibit, The Runaway Girl, depicts that stranger in a strange land. Hair long past her waist, dainty valise in hand, dressed in a short skirt predating the sixties by almost three decades, she appears to walk, even mince, on aquamarine water, or perhaps a cloud. Just behind her, a crudely drawn figure swims through something like wavy concrete. This girl is the intrepid fool of a dark fairytale, ignorant of what lies ahead, determined to escape what lies behind. She can walk faster than her pursuer can swim. That does not mean she can get where she intends to go or that she can escape what she leaves behind, as almost every artwork Bourgeois ever made expresses in some way.

Bourgeois abandoned, as she put it, her family of origin—father, older sister, younger brother—when she left France shortly before the war. Because her husband was already well-established in the New York art world, Bourgeois was neither materially nor culturally impoverished when she arrived. Armed with her own excellent lycée education, she’d also had several semesters at the Sorbonne studying mathematics and subsequent art study at various ateliers in Paris. Also important to her sense of self was her work experience repairing precious tapestries in her family’s business and then running her own small gallery for a few months before meeting her husband.

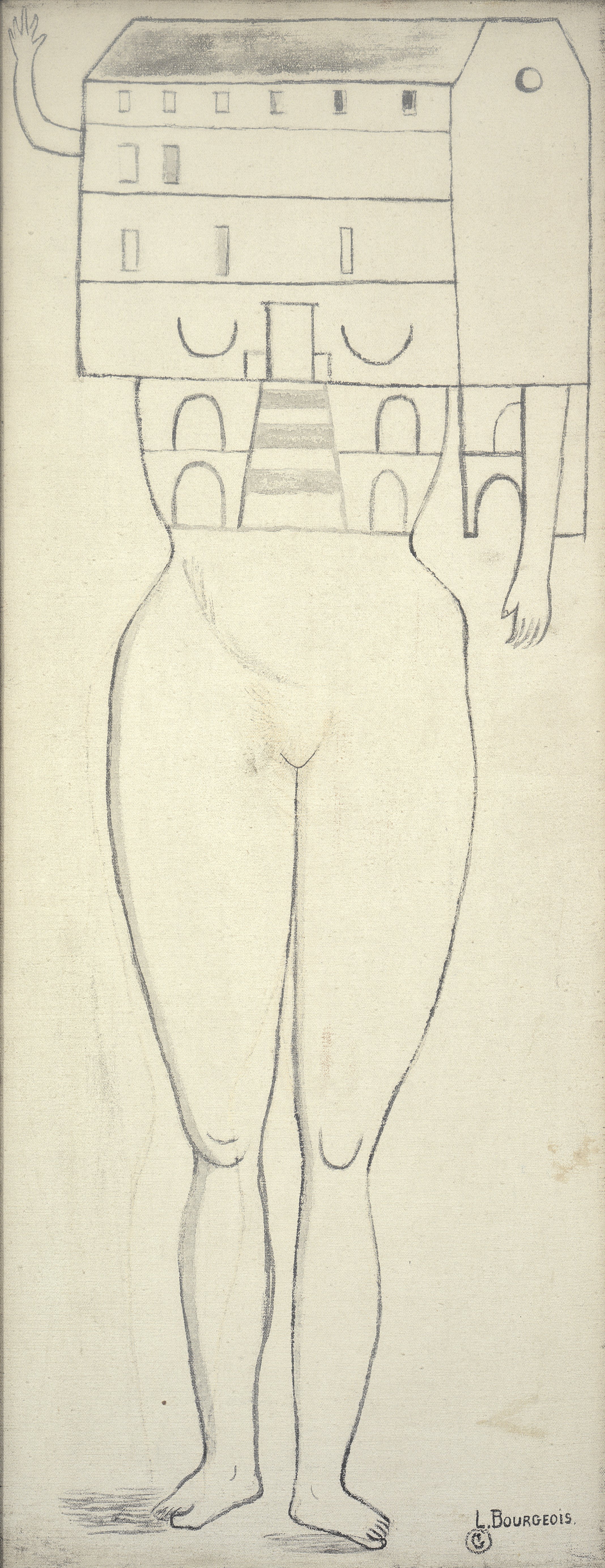

Perhaps the most mordant commentary on her new life as an American wife and mother in the exhibit is the series Femme Maison. The largest, Fallen Woman, shows a horizontal woman cut in half by a building, as if in a magic trick, her head with its long hair at one end, her balletic legs, toes pointed, poking out of the other. Others are more revealing, perhaps betraying that, during this period, Bourgeois was torn between her young marriage and a love affair with a Chilean artist, as Robert Storr uncovered in his exhaustive monograph, Intimate Geometries. In another painting, a woman is impaled by a building while her naked lower half, shapely and generically feminine, is exposed. The saddest shows a woman’s bare legs and exposed vulva emerging from a dark building; three arms emerge from the top, two seeming to belong to a woman, the one beneath perhaps a man’s. She has fallen and the house has caught her, but we don’t know whether those arms are waving or flailing.

If the Femme Maison series are paintings of despair or rage or rebellion, they are playful enough, particularly with the tropes of surrealism, to obscure this. (Bourgeois used one on the invitation for an exhibit of her work in 1947.) Witty, too, but also revealing, is a letterpress book she made, He Disappeared in Complete Silence. In Plate 7, “A man was angry at his wife, he cut her in pieces, he made a stew of her. Then he telephoned to his friends and asked them for a cocktail-and-stew party.” Most telling is the accompanying, largely abstract drawing of a figure on the roof near a water tower: possibly a sculpture, possibly the artist with her swath of long hair. “Then all came and had a good time,” is the conclusion. The suggestion is that the husband is murderous because his wife is up on the roof making art, but we have to ask if it is really the husband who wants to commit the cannibalism. Anticipating her sculpture The Destruction of the Father, with its unsparing depiction of an overbearing father as meal, this parable sets spinning all her themes, making them palatable, so to speak, amusing enough, confusing enough, that aggression is expressed without being owned.

It was, of course, Bourgeois who was in danger of disappearing into complete silence, consumed by not just family duties but her own inner conflict. That drama is, for the most part, presented obliquely in these early paintings, the work of which concluded in 1949. “I could express much deeper things in three dimensions,” Bourgeois said thirty years later, to the curator Deborah Wye as they prepared for a Museum of the Modern Art retrospective. The two lone sculptures, tucked into a corner of this show, bear out that belief. Dagger Child, first exhibited in 1949, is one of a series of “personages,” modeled on people in Bourgeois’s life. Tall, spindly, designed to be bolted into the floor, the sculpture feels at once delicate and menacing, its most realistic element a dagger with a chilling dot of red held at chest level. Composed of four visible layers, the piece suggests that aggression is solidifying. This is not a figure of an inner self about to fly apart or fall or disappear, as so often seen in the paintings. The second sculpture, Femme Volage (fickle woman), composed of dozens of moving parts held together by a central pole functioning as a spine, suggests a propulsive energy surely on a collision course with the menace of Dagger Child.

Beauty is not what interests her, nor verisimilitude, nor developing a style to compete with the boys. “Art is not about art,” Bourgeois said [. …] “Art is about life.”

IF THE PAINTINGS exhibited here flicker with Bourgeois’s protean talent, they do not, on their own, explain the interruption of her career that would follow. Despite her already-apparent genius for sculpture, and despite selling one of the personages to the Museum of Modern Art, Bourgeois entered a deep crisis as she approached her fifth decade. The unexpected death of her father in 1951 led to a suicide attempt and then a spiral of depression. When Bourgeois entered psychoanalysis in January 1952, she was having difficulty leaving the house and was sometimes accompanied by one of her sons on her subway trip to the Upper West Side.

Where the exhibit trails off, with the end of Bourgeois’s painting life, is where her career might very well have ended. The catalog of the exhibit places Bourgeois in an artistic context, first in France and then the US, but does not take up her self-referential web of symbols in depth. “There’s no getting away from the fact that many of her paintings are very odd and really show what an outlier Bourgeois was,” Briony Fer writes in her strangely dismissive contribution to the catalog. Since so many of these paintings are ultimately self-portraits, we might more usefully see this decade of painting as a unique Künstlerroman, the flaring and flickering of a manic talent taking shape but always on the cusp of being snuffed out.

Few other artists are more associated with psychoanalysis than Bourgeois, who kept hundreds of pages of notes on the process. This exhibit allows us an unprecedented opportunity to see as a discrete period the work she made before undergoing treatment. Bourgeois had turned from mathematics to art at twenty-two when her mother died. Twenty years later, she gave up on art after her father died. From this we might infer how powerfully her parents were involved in her artmaking, the permission she gave herself, the permission she retracted, the camouflage she used. “Some of us are so obsessed with the past we almost die of it,” Bourgeois began a 1982 essay titled “Child Abuse,” published in Art Forum. Her conclusion was, “Every day you have to abandon the past or accept it and then if you cannot accept it you become a sculptor.” A gifted middle child who was supposed to be a son, she never forgave her mother for making her a pawn, nor her father for his philandering. The story might be reductive, but it was the engine of her art.

She found the strength not to die, but the road to her unconscious—and ultimately her art—was filled with detours. She opened a shop selling prints and books to pay for the analysis, contemplated becoming an art therapist, and spent a year teaching public school. She kept extensive journals and drew all night when she couldn’t sleep. Her insomnia, her panic attacks, her difficulties with others persisted. But instead of fading into obscurity, she became, as she approached old age, an icon whose celebrity sometimes eclipsed her complicated and astonishing art.

‘Louise Bourgeois: Paintings’ is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art April 12, 2022—August 7, 2022