YEARS AGO, MY parents gave me Step Aside, Pops by Kate Beaton for Christmas. It was a collection of short, witty comics about literature, history, and feminism, a follow-up to the best-selling 2011 collection Hark! A Vagrant, which began as a webcomic Beaton created while studying history and anthropology in college. I obsessed over Step Aside, Pops for the rest of my adolescence. I read it late at night, feeling delighted and understood; I was sixteen and pretentious enough to crack up over illustrated parodies of people like Byron and Shelley. I told my friends, “When I get a coffee table, this’ll be my coffee table book!”

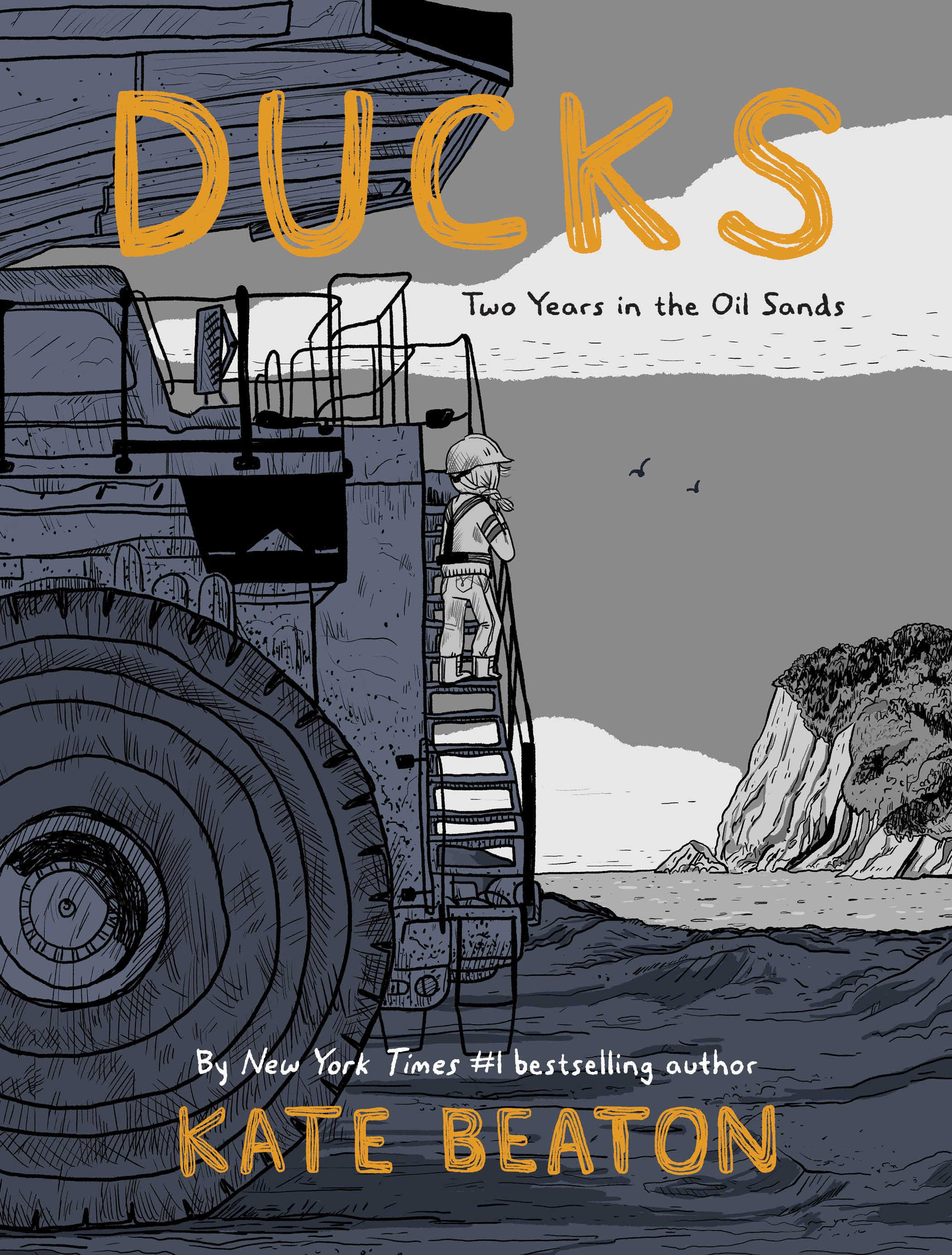

Seven years after the publication of Step Aside, Pops, Beaton has returned with a marked change in tone. Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands is a graphic memoir about two of the most traumatic years of Beaton’s life. At twenty-two, she traveled across Canada for a job in the Alberta oil sands. Why? you might ask. Why not? She’d just graduated from college and knew there was little opportunity in her tiny Nova Scotia town. Right at the start, she tells us, “The only message we got about a better future was that we had to leave home to have one. We did not question it, because this is the have-not region of a have-not province, and it has not boomed here in generations.”

Beaton, referred to throughout as Katie, takes a job in a Syncrude “tool crib,” handing out tools to workers. The reality of female existence in such a highly masculine environment presents itself immediately. The workers—virtually all male and decades older than Katie—derail conversations with her toward topics of dating, or sex, or her appearance. Some pass by the tool booth only to stare at her, seemingly amazed to be in the presence of a young woman. This apparent titillation nauseates Katie, and she tells an older female coworker, “All you need here is to be a woman. You stick out, and that’s all it takes . . .” Her coworker responds, “I think that’s pretty cynical.” Even in spaces where she should find camaraderie, Katie often feels out of place, hysterical, and ashamed.

Acceptance from her male peers only arises as she becomes more permissible, sitting quietly alongside them as they discuss the sexual value of women. When one male friend comments that she’s the type of woman who “doesn’t take any shit,” Katie quietly insists, “I take a lot of shit.” Yet despite her attempts at friendship and the working-class background she shares with these men, she learns they will never fully accept her the way they accept one another. They still ogle her, try to cajole her into dates, jiggle her locked doorknob at night. The oil sands prove to be too much for Katie, and a series of increasingly traumatic incidents forces her to leave.

In Ducks, Beaton has created not a precise, chronological chain of events but a carefully curated collage of her experiences over those two years, showing us more feelings than she does incidents. The sardonic humor of her earlier comics is still present, but the story relies more on nuances of dialogue and metaphor. Everything is there for a reason and everything means something, from Katie’s tears at the sight of the Northern Lights to the three hundred ducks that drown in an oil pond. We learn little of the period that follows her first stint in the oil sands, except that she worked at the Maritime Museum of British Columbia, was underpaid and unsatisfied, and eventually decided to go back to Alberta. What we do know is that this return is as necessary as it is tragic, and that any job is a good job, even a bad one.

By Kate Beaton.

Her second stretch at the oil sands is spent in an office, removing her from the watchful eyes of male workers and presenting her with ample time for self-reflection. As accusations of harassment and misogyny at the sands come to light, a woman journalist contacts her for a phone interview. Katie is so frustrated by the journalist’s apparent fascination with her abuse and readiness to condemn the miners that she remarks to a friend, “[People like her] don’t think that the loneliness and homesickness and boredom and lack of women around would affect their brother or husband or dad the same way.” Later, she adds, “Am I defending them? I don’t know, just, they are still my people. Even at their worst, they’re more mine than she is.”

Earlier in the book, Katie laments to a mine worker, “I want my people. My people don’t want me.” The tenuous relationship she shares with the men of the oil sands is riddled with contradictions. The respect and affection she feels for some of the workers is not something she can dole out freely. It’s as Sylvia Plath once wrote in her journal: “My consuming interest in men and their lives is often misconstrued as a desire to seduce them, or as an invitation to intimacy. [. . .] I want to be able to sleep in an open field, to travel west, to walk freely at night . . .” In another instance, a coworker complains to Katie about the special treatment given to “idiot sons” of the corporate bosses, and she replies, “I would love to be someone’s idiot son.” What she yearns for is somewhere in between safety, anonymity, and approval—but as a woman in what one of her bosses calls “a man’s world,” she finds that those three things remain just outside of her grasp.

“I would love to be somebody’s idiot son.”

Beaton refuses to pick sides. In a thoughtful afterword, she mentions, “I learned you can have both good and bad at the same time in the same place, and the oil sands defy any easy characterization.” Ducks shows us the devastating impact the Canadian oil industry has had on the environment and First Nations communities, quoting Cree elder Celina Harpe: “Everything’s ruined, our lives around our lands are ruined, our water, the air, everything.” Nevertheless, Beaton acknowledges that the workers—many cancer-ridden themselves—cannot shoulder all the blame. When a guerilla group of eco-activists clog the site’s pipes, an irate worker storms into Katie’s office. “And who do you think cleans that up?” he shouts, jabbing a newspaper headline about the protest. “Who puts their life on the line to unclog that pipe? I tell you it sure as fuck isn’t the president of Shell!”

Full of the insight of hindsight and the sorrowful anger of the young working class, Ducks triumphs in its honesty. The angrier Katie becomes with her treatment in the oil sands, the more she comes to understand why such cruelty exists. A thoughtful reader will come away from the experience with many different opinions, none of them quite able to exist alongside the others, and that is how it should be. There is no answer. There is no solution. There are only people, and people are such inconsistent animals.

I’ll leave you with the scene that left the greatest mark on me: Katie, lugging trash to a dumpster in the middle of the night, stumbles upon a three-legged fox. She is filled with an immediate, inexplicable rage at its presence on-site. “You stupid god damn fox,” she yells at it. “What are you going to do when you lose another leg!? What do you think is going to happen?” Though she manages to chase it away for a moment, her fury is futile; the oil sands are the fox’s home. Life is not as simple as staying or leaving.