TRANS WOMEN MOTHER each other when nobody else will. Cecilia Gentili is a legend among New York trans women; there must be hundreds for whom she is “mom.” It’s a hard role to play for trans women whose relationship to their own mothers is fraught. As Gentili says of hers, “I saw in your eyes so many times the wish that I was not your child.” While mom might not be the best term, one thing trans mothering may share with other maternal roles is that it’s asymmetrical. The trans mom has to appear uncomplicated. The trans daughter is supposed to be the hot mess, to take up all the emotional bandwidth.

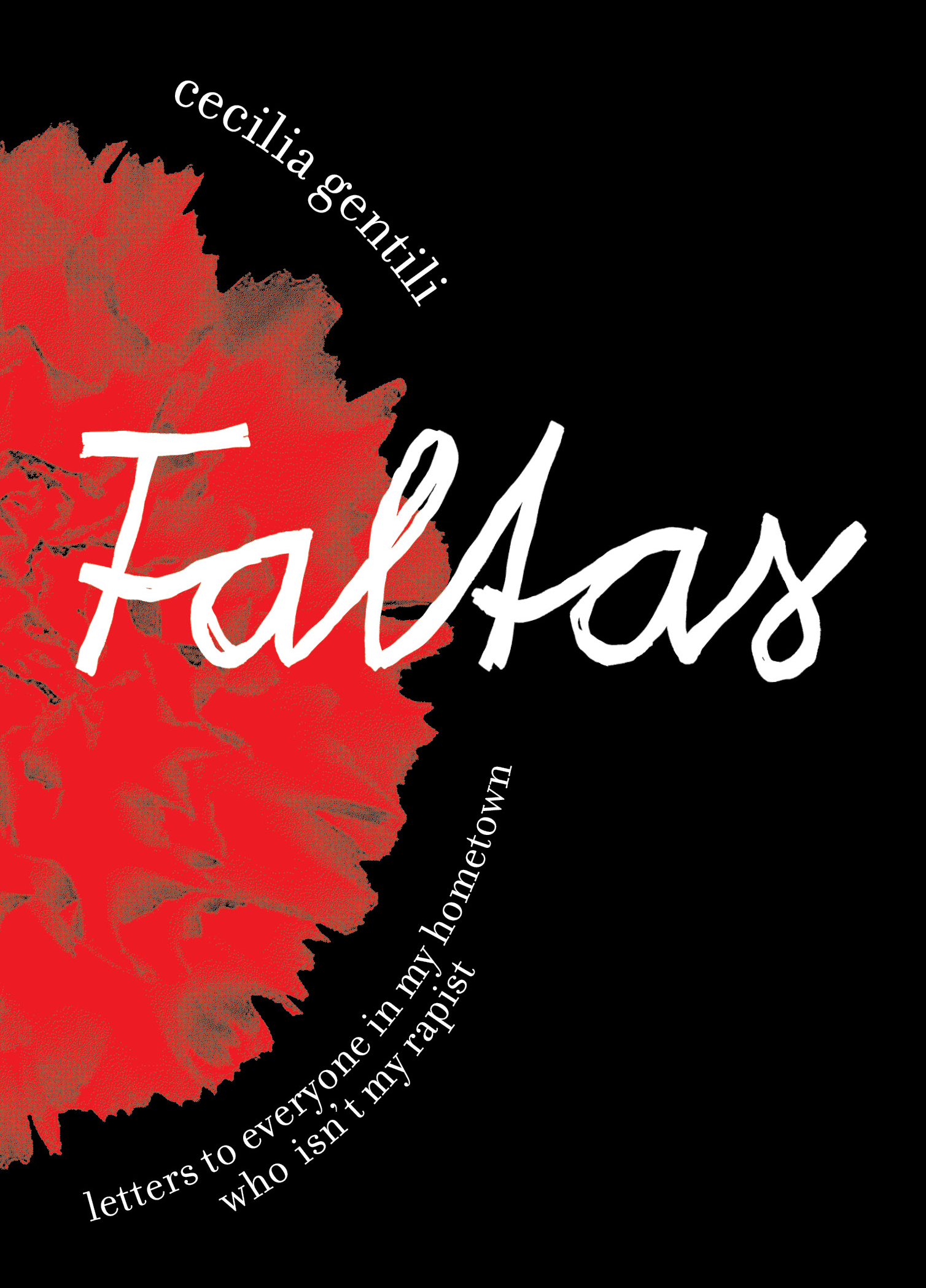

It’s a revelation, then, to read this emotionally and ethically complex account of Gentili’s early life. The minimum requirement for eventually becoming a trans mom is keeping oneself alive. She did, and this is how. Told through a series of letters, Faltas is the story of how she survived her early years in provincial Argentina. It’s a story of enduring small-town life as some kind of faggot.

Faggot is the word Gentili uses to translate maricón, and it’s a better approximation than gay. You can be gay and hide it, but if you are a faggot, everyone knows or thinks they know. In her case, faggot wasn’t quite the word. On the principle that you can use a slur if it’s something you get called, trans women can use the f-word. It’s how many of us appear to the people around us until we figure it out. The people who think they are normal think of the faggot as a fault (faltas) and also as someone at fault.

Faltas is a perceptive study of the sexual economy of a small town seen from the point of view of faggots and whores—where whore means any woman who can be accused of using her sexuality, even if just for her own pleasure. Like the faggot, the whore is trying to survive. Both might also be trying to acquire and exercise a morsel of agency, even of power. “I already knew that men could be controlled by sex,” Gentili writes, “but it was Mary who showed me this could become an art, a field of expertise.” But in the end, with faggots or whores: “We were both disposable.”

Among faggots, little Cecilia finds both friends and rivals. She is not funny, fun, or artistic. She “couldn’t seem to find a way to make faggotry relevant.” She is not too flagrant, either, and so is not the one who is murdered. She finds a friend, but even in that intimacy there are faultlines. When power puts you on the bottom of the heap, it’s appealing to find even one person you can push beneath you. As she writes to her childhood fag friend, “Yes, you were more ‘likeable’ than I was. But the ones that mattered, the handsome men that we really wanted to be liked by, they liked me more. I started to see myself as better than you. I was magnanimous about it.”

Straight cis women sometimes think they have a monopoly on femininity, that ambivalent gift…

Even more faulty are her connections to the cis women the town considers whores. Faltas opens with the extraordinary tale of little Cecilia’s connection to her father’s mistress, who lets her wear her dresses and makeup: “We were comfortable with each other. We were aware of each other’s secrets and knew what we both needed and what it cost, both to our well-being and our consciences.” But the mistress indulges Cecilia only to drive a wedge between her and her mother. Transsexuality is an exploitable condition. Both cis women and men take advantage of Cecilia’s desperate, basic need. “What a fucking fight it is to be. Just be.”

The apparently respectable cis women look down on faggots and whores alike. From her place in the disavowed underbelly of the town’s sexual economy, Cecilia acquires perspective: “The ring they flash with arrogance is the symbol of their captivity.” Cis women end up pregnant, or married, or sort-of married. One cups her hand around her vulva and tells Cecilia that it’s a power she will never have. But Cecilia has another power, weak though it may be, that they sometimes envy.

THERE’S NO LETTER to her rapist in Faltas, but he is central to it. This man sees the femininity of this child that everyone else is demanding that she repress—and he exploits it. “He understood my femininity as normal and used that too.” For years. “He gave me permission to be.” Of course, men exploit cis girls and women by making them feel seen, but then at least the rest of the world is also acknowledging their femininity. For the nascent transsexual woman, there’s not even that, and it’s even more exploitable. When the entire world is refusing to let you be—a man has a lot of power by giving you the impression that he will. So long as he can get his dick in something. “I sucked it just so I could keep listening to his deep voice calling me ‘my girl.’”

Gentili does not let this man—or anyone—off the hook for exploiting her vulnerability, yet she does not cast herself as an innocent victim. It’s a difficult set of thoughts and emotions to hold at once, but then, isn’t this one of the great tasks for any oppressed people? To look with a cold eye at our complicity with what has power over us? And yet the fault is entirely his. “What I needed was not just to be seen as a girl, but to be treated like one, and that he didn’t do. He treated me like you treat a woman.”

Faltas is a story of learning to work what little power one has. Straight cis women sometimes think they have a monopoly on femininity, that ambivalent gift that is a source of both power and powerlessness. That’s a delusion that makes faggots and transsexual women smile. Ostensibly straight men consider us part of an available femininity, too, consider us willing or unwilling holes for their dicks. Femininity is distributed across other bodies.

Solidarity is hard in a sexual economy that works to pit the least powerful against each other, that only recognizes relations of domination and treats the dominated as next to nothing. A man who is abusing Cecilia forces himself also on a cis girl. When the girl complains, she is the one held at fault. Cecilia says nothing. As she writes to this girl, “It was just not convenient for me to help you.” And it would not have done any good. “Maybe I also saw you as disposable. If I did, it was because I saw myself that way.”

Some things are open secrets: That a child is being abused. That straight men are having sex that isn’t with cis women. That someone was murdered for their sexuality. Gentili asks more than once, How did this all seem normal? It seemed normal because the sexual economy is built on playing one kind of disposability against another. The power structure is thinly veiled in a hypocrisy nobody tries too hard to hide, and if one is trans, “lying [is] exactly what [is] required.” Flimsy moral platitudes are backed by violence. It’s a childhood and adolescence a budding transsexual might well not have survived. Negotiating its fissures inculcates its own worldview. “I always thought: I may get murdered tonight, so it doesn’t matter. I had learned to evaluate risk on a whole other level than you and most of the people I knew.”

An outstanding quality of Faltas is that it avoids melodrama and moralizing. What it depicts is not a fallen world but the ordinary state of things, and not just in Argentina late last century. It even has space for moments of peace and pleasure. On one glorious page, a young Cecilia learns, from an unusually attentive lover, “that my dick, even mine, could be used during sex. Contrary to what I thought, it had nothing to do with making me a man. He gave my body pleasure and, in the pleasure, it became mine.”