THE FIGHT TO pass the Nineteeth Amendment was full of firsts. There was the first women’s march on Washington: eight thousand women paraded along Pennsylvania Avenue on the eve of Woodrow Wilson’s presidential inauguration in March 1913. There was the first use of picketing as a form of political protest: suffragists took part in “Silent Sentinels” in front of the White House in 1917 to highlight President Wilson’s hypocrisy in “making the world safe for democracy” while abrogating the civil liberties of women. And there was the first memorial service held for a woman in the Capitol, which honored Inez Milholland, a labor lawyer and leader of the suffrage movement whose anemia finally did her in on a grueling speaking tour.

Suffs, a new, bursting-at-the-seams musical confection from The Public Theater, engirdles all this and more. With its all-women-and-nonbinary cast, it also has the distinction of being the first musical about the uncompromising suffragist Alice Paul. Shaina Taub, who plays Paul, also wrote the book, lyrics, and music for Suffs. Like another famous musical about certain founding fathers that got its start at The Public, Suffs uses color-conscious casting to implicitly critique the nation’s foundational racism. Philippa Soo, who originated the role of Eliza Hamilton in Hamilton, is another binding agent; in Suffs, she plays the savvy Milholland. Lin-Manuel Miranda himself has even given the show his seal of approval, tweeting that Suffs is “gobsmackingly incredible.” Like Hamilton, Suffs strives to offer a usable past: a version of US history that annotates its shortcomings while making the case for a more inclusive society.

Before a single suffragist has had a chance to speak in her own voice, we hear from their detractors in a vaudeville-style number that sees the eighteen cast members, dressed up as vulgar misogynists, dress down free-thinking radical feminists. They lob insults at the audience that are as contradictory as they are passé: the women are both viragoes and have “ugly little silhouette[s].”

Suffs opens in 1913. Carrie Chapmann Catt (a stately Jean Colella) has taken up the mantle from Susan B. Anthony to lead the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). (Historians may quibble here with the play’s compression of events; Catt left NAWSA in 1904 to take care of her sick husband and wasn’t reinstalled as its head until 1915.) Meanwhile, Alice Paul, twenty-seven and a newly minted PhD, has come to D.C. to seek an audience with Catt and make the case for pursuing a federal woman suffrage amendment. As played by Taub, Paul is possessed of the pulverizing-all-obstacles energy of Joan of Arc. (“Why was I born with a voice this loud, but a mouth the world wants to keep shut?” goes one refrain.) Catt and Paul are nominally fighting for the same thing, but the two women are temperamental opposites. Catt advocates a moderate approach to securing the vote for women —“organize, agitate, educate,” goes her motto, “not antagonize, irritate, enervate” —while Paul is a pot-stirrer who won’t be satisfied with “incremental crumbs.” She proposes that NAWSA seize the opportunity of Wilson’s imminent inauguration to plan a women’s march on Washington. Catt demurs, but Paul forges ahead with her vision. (Here again, there’s some historical embellishment: Paul had managed to persuade NAWSA in 1912 to form a lobbying arm and set her up with an annual lobbying budget. The musical seems intent on generating perhaps more friction than is strictly necessary.)

As Paul recruits others to join her suffrage march planning committee, we meet Milholland, played by Soo as a charismatic AOC-like figure on her way to becoming a lawyer. As soon as she appears on the scene, holding forth to a group of bohemians in a blazer and skirt of resplendent periwinkle (Pantone’s color of 2022), we hear from Paul that she is the “poster girl for radicalism” and “a highly coveted speaker in the hotbed of reform” (the musical is often a bit too ready to supply us with these SparkNotes summaries). Paul lacks the magnetism of Milholland, who has the idea to lead the march on a white steed, but more than makes up for it in organizing know-how. Lucy Burns (Ally Bonino), a friend of Paul’s from college, is a quick convert to the cause, as is Doris Stevens (Nadia Dandashi), a wet-behind-the-ears Oberlin graduate who will go on to write the group history Jailed for Freedom: American Women Win the Vote. There’s also Ruza Wenclawska (Hannah Cruz), a working-class straight shooter who, in the words of a wealthy patroness, puts the “rage” in “suffragette.” For a while, Suffs crackles with the energy of women flying by the seat of their pants.

The first fissure in the new group announces itself in the form of a question: What to do with Black women who want to march? Some of the white women think that the Black women should withdraw so as not to alienate NAWSA’s Southern donors, but Paul thinks they should march in a separate contingent at the back of the line. Milholland calls Paul out on this: “Oh, that’s rich coming from you, the leader of a movement for equality.” So committed is Paul to the idea that she has to be “the one to finish the fight” that she becomes a “white feminist,” or someone who, in the words of Pakistani American writer and activist Rafia Zakaria, pays lip service to the idea of progress for all women, “but [who] fails to cede space to the feminists of color who have been ignored, erased, or excluded from the feminist movement.” In a splendid aria, “Wait My Turn,” the journalist and civil rights activist Ida B. Wells (Nikki M. James) asks Paul: “Do you not realize you’re not free until I’m free?”

That work of lifting each other up while holding on to your dignity depicted in for colored girls is very different from the feminist energy of Suffs.

FAST FORWARD THREE years. Paul & Co. have officially splintered from NAWSA and formed their own organization, the National Woman’s Party. In 1917, they shock the nation by picketing the White House during wartime. We see them hold up signs using President Wilson’s own words against him and demanding the right to vote. Many are subsequently arrested on charges of obstructing sidewalk traffic. In one especially harrowing sequence, Paul, Burns, Stevens, and Wenclawska are rounded up and imprisoned in the Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia, where they go on hunger strike and are brutally force-fed with tubes up their noses.

In a dank cell, Paul hallucinates from weakness—the only time her resolve slips. President Wilson (Grace McLean) wants her committed and dispatches a psychiatrist to evaluate her. In one of the play’s more exquisite moments, Paul imagines the doctor as her late friend, Inez Milholland (both characters are played by Philippa Soo). “You don’t always have to be the strong one,” she sings to Paul, “you’re allowed to admit you have a shadow of a doubt.” Paul unburdens herself, confessing as much to the doctor and, presto change-o, the inmates are released and ready to burn an effigy of Wilson across the White House. The play’s gears here click too quickly back to efficiency; Suffs would have been stronger if it, too, had shown us more of its “anxious soul,” revealed here only in Paul’s half-lucid colloquy with a spirit and in an eleventh-hour exit interview in which Lucy Burns tells Paul that she’s worn-out and “not marching anymore.”

Tasked with dramatizing suppressed US history through showtunes, works such as Suffs can get bogged down in exposition and earnest messages. The result is worthy, without a doubt, but not transcendent.

THE LAST THING you see in Taub’s musical is a line of women spanning several generations, forming a united front. They hold hands in one long, defiant chain—they could be on a march—and sing-chant “the work is never over” and “the young are at the gates.” Ntozake Shange’s polyvocal for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf, which opened on Broadway more than forty years ago and was revived in spring of 2022 by the Booth Theater, abjures the line for the circle.

Shange, who passed away in 2018, titled the preface to her unconventional play “a mandala for colored girls.” That description hints at what makes her “choreopoem” so refreshingly different from Suffs. Her seven Ladies of the rainbow form bonds not from political expediency or ideology but from games of Little Sally Walker, music, dance, and playful ritual. Their bodies move as a contracting heartbeat. When one of them is in distress, the others will gather around her for support before blooming away. That work of lifting each other up while holding on to your dignity depicted in for colored girls is very different from the feminist energy of Suffs.

Born Paulette Williams, Shange gave herself a new Xhosa name in 1971, meaning “she who comes with her own things” and “she who walks like a lion.” Shange acknowledged that for colored girls drew from her immersion in the women’s studies program at Sonoma State College, where she worked for over three years. Certain moments of the play, like Sechita, about an idealized dance hall girl, are directly informed by Shange’s study of “the mythology of women from antiquity to the present day.” And yet, for colored girls never feels like an animated history lesson. Combining dance and spoken-word poetry, the ninety-minute play is less invested in extending any kind of canon than in celebrating the multifarious joy and pain of moving through the world in a Black body. Early performances were staged in bars, cafes, and poetry centers in California. Word of mouth then helped the play transfer to Henry Street, where the cast expanded from five to seven women, before moving to the Public, and finally to the Booth Theater on Broadway in 1976. Shange herself acted in the play and said that she intended to immerse audiences in “[Black women’s] struggle to become all that is forbidden by our environment, all that is forfeited by our gender, all that we have forgotten.”

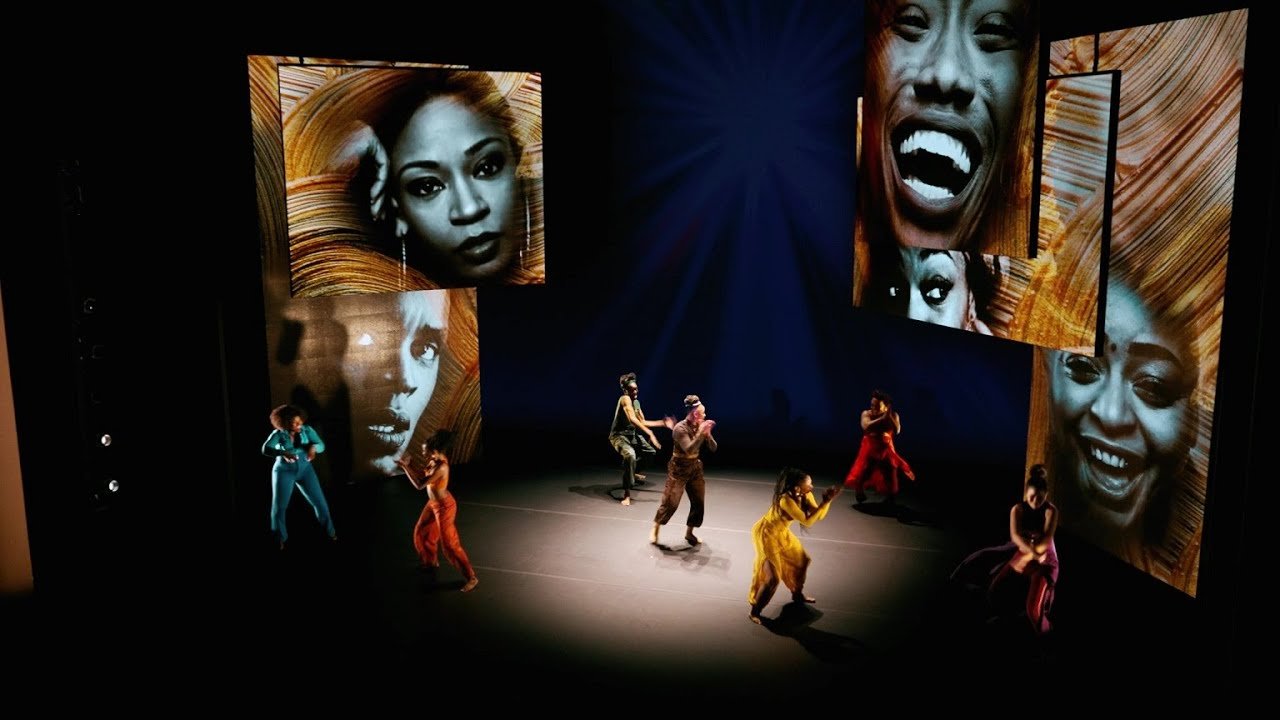

That recuperative mission was evident in 2019, when Leah C. Gardiner produced for colored girls at The Public, surrounding audiences with mirrored panels, wind chimes, and a disco ball. Camille A. Brown, who choreographed The Public’s production, directs the revival at the Booth, making her the first Black woman to both direct and choreograph a Broadway show in more than sixty-five years. The set of the new production, which features many of the same actors from The Public’s production, is deceptively austere. Instead of mirrors and chimes, five rectangular screens project pink flower petals in close-up, later replaced by blowups of the Ladies’ faces. Some are broadly smiling, one wears the ghost of a frown, another has a gaze that could level you at ten paces. (Set design is by Myung Hee Cho, and Aaron Rhyne did the projections).

We are inducted into the play with a recording of Shange saying: “Imagine all the stories we could tell about the funny looking lil colored girls, and the sophisticated lil colored girls, and the pretty lil colored girls, the ones just like you!” Tendayi Kuumba’s Lady, in a midriff-baring brown shirt and pants, then takes center stage to a table-thumping beat (Martha Redbone and Aaron Whitby composed the score) and shakes out her limbs, appearing at times to be shadowboxing an unseen antagonist. She’s backlit by a star, and a trick of lighting makes it seem as if that is her point of origin; she’s a message being beamed back to us from the future. The Lady in Brown invokes a muse to “sing a Black girl’s song.” The Black girls for whom Shange has written this poem are “half-notes scattered,” and the play is invested in resuturing them to their rhythm. The Lady in Brown is soon joined on stage by six other Black women, each clothed in a different color of the rainbow and each an outsider. Geographically, they’re “outside Chicago,” “outside Houston,” “outside Detroit,” and so on, but a sense of being ontological hitchhikers shadows them as well: watch how they groove into and out of one another’s stories.

In The Public’s 2019 production, the women wore diaphanous costumes printed with the faces of Black women. (Casting my mind back to Suffs, costume designer Toni-Leslie James uses mostly white, sedate gray, or blue. Why not make more striking use of colors, especially when American suffrage groups were known to have favored purple for signifying dignity and loyalty, green for hope, and gold for enlightenment?) The costumes in the Broadway production of for colored girls, designed by Sarafina Bush, are just this side of athleisure and telegraph not so much sisterly solidarity as something more fluid. Their kinetic energy is palpable in every freewheeling movement, every twist and turn. Most audiences won’t necessarily be aware of Shange’s stage direction that “each lady dances as if catching a disease from the lady next to her.” Certainly, the women’s enthusiasm for life and loving is infectious. “We gotta dance to keep from cryin,” says D. Woods’s Lady in Yellow, and the Lady in Brown adds, “We gotta dance to keep from dyin.” Moments like these—where it becomes difficult to distinguish where one woman’s story ends and another’s begins, where one color of the rainbow melts into another—loop throughout the play. The song cycle that follows is full of peaks and valleys, touching on everything from a sexual awakening at a high school graduation to a trio of women falling in love with the same man to another woman being poleaxed with grief over the death of her children. There’s also an anthemic breakup letter to end all letters that elicited many finger snaps on the day I saw the show. Even with cuts to some of the original poem (“positive,” a conversation about contracting HIV, is notably missing), for colored girls sings the (Black feminist) body electric.

The cast is uniformly strong, but I must single out three members. Tendayi Kuumba as the Lady in Brown gives a virtuosic performance of “Toussaint,” which recounts her childhood infatuation with the Haitian revolutionary Toussaint L’Ouverture, a Black man “who refused to be a slave & didn’t low no white man to tell him nothin.” L’Ouverture “waz the beginnin uv reality for me,” she says and regales us with her discovery of the historical figure while mainlining tomes for a reading contest. Having devoured fifteen books in three weeks, she wins the contest handily, only to find out that she has been disqualified after the judges find out she read something from the verboten Adult Reading Room. Undeterred, the Lady in Brown takes Toussaint home with her, where he “bec[o]me[s] my secret lover at the age of 8.” She dreams of running away with her imaginary friend to Haiti and legs it as far as north St. Louis. There, she meets “some tacky ol boy” wearing “skidded out cordoroy pants [and] a striped teashirt wid holes in both elbows.” Kuumba deftly plays both parts; one second, she’s her wide-eyed eight-year-old runaway self, and the next, she’s Toussaint Jones, who’s just coming into his own swagger. The encounter marks the dissolution of one fantasy and the birth of another.

The towering Okwui Okpokwasili (the actor literally stands at least a head taller than the others) also delivers a moving performance as the Lady in Green, of “somebody almost walked off wid alla my stuff.” After that first line, the audience around me erupted into applause for what seemed like a full minute; such is its renowned status as a spiky, bittersweet rebuke of a former lover. It’s ostensibly addressed to a variety of men who have spurned the Lady in Green—or perhaps, better to say, a composite of them: “a man whose ego walked around like Rodan’s shadow,” “a man faster n my innocence,” “a lover I made too much room for.”

Ideas jump around from one lady to another without missing a beat; what follows the Lady in Green’s tale is a comic interlude where several exes make bumbling excuses for cheating (they are each played by one of the Ladies and includes an unmissable impersonation of a certain former president). Finally, the deaf actor Alexandria Wailes gives a dazzling performance as the Lady in Purple, who inhabits many roles, but none more stunning than that of the mythical Sechita, an amalgamation of earth goddess, Creole dancer, and carnival worker. In a departure from the original script, the Lady in Purple ASL-signs and dances her way through the life of this dance hall girl, while Amara Granderson’s Lady in Orange supplies narration: she makes us see Sechita “catchin stars tween her toes.” Instead of acting as flypaper for a surfeit of facts, Shange’s play is calibrated to make us marvel as much about what we don’t know—maybe can’t ever know—as what we do know about any one person. for colored girls gives us a parallax view of these rainbow figures, never staying too long in one place, never fully identical to itself.

In its ecstatic enjambments, in its treatment of themes from domestic violence to toxic masculinity, in its revelry of bodies dancing in close proximity after more than two years of enforced isolation, for colored girls is a play that addresses the current moment. Its unflinching portrayals of rape and abortion (a sensation that Stacey Sargeant’s Lady in Blue likens to “metal horses gnawin my womb”) were ahead of its time. Watching it in 2022 gives the sense that we are only now catching up to Shange—all that she metabolized, prophesied, and captured with poetic precision and elision. She did encounter some backlash, when earlier iterations of the play opened, for portraying Black men as “unsympathetic” characters. That concern, in the wake of #MeToo, seems less alive today, and this production—unlike some earlier ones—uses no men. The focus is resolutely on Black women.

The play ends with a healing circle, “a layin on of hands” that follows the most wrenching recitation in the entire poem, a mother’s lament about losing her children to a vengeful lover. The monologue is performed by an eight-months-pregnant Kenita R. Miller and the stillness she conjures feels all the more stunning after several consecutive minutes of nonstop movement; it hits you like a truck. As a piece of live theatre, for colored girls plugs you into a wall socket of spiritual energy, making you a grateful witness to the pulsing pain and onrushing pleasure of these women’s bodies.