Some artists dedicate a whole career to the scrutiny of a particular feeling. Proust did nostalgia; Updike did extracurricular lust. The cartoonist Roz Chast does anxiety. Take, for example, “The Party, After You Left,” a single-panel cartoon of a group of people milling about on a New York rooftop at night. “Thank God she’s gone!” someone says. A friend agrees: “Now we can really have some fun!” Across the panel, a man asks, “Would anyone here like to try this very, very safe, short-acting, non-addictive, extremely fantastic new drug?” Someone else waves frantically off-panel: “Look who just walked in! Yo! JESUS!! BUDDHA!! OVER HERE!!!” The flavors of anxiety here—social, good-girl, hypochondriacal, philosophical—appear in nearly all of Chast’s work. Once coded as Jewish or immigrant, these anxieties have now—after several years of lunatics in charge and both coasts burning and the possibility that a poorly planned social event will kill beloved grandparents—gone mainstream.

At root, Chast is interested in how the small and piddling self can exist in the large and daunting world. This is an anxiety of childhood, and so unsurprisingly much treated by cartoonists, who are the closest thing we have to socially licensed permanent children. Some cartoonists choose to cast small and piddling moments against fantastically large backdrops. Think of Calvin and Hobbes, where first-grade math class is imagined to take place in outer space, or of New Yorker cartoons that involve monsters, flying humans, or heaven’s pearly gates. Chast avoids this typical enlargement of imagination. Her tack is the opposite: big-picture stuff at banal scale, soup-can existentialism. Among her favorite props are toasters, thank-you cards, grocery lists, junk. A full-page spread titled “First-Period Algebra” follows the typical gag of a bored student daydreaming. He starts off okay, on an otherworldly planet. Then his thoughts turn to different types of mustard. “This is SAD!” he decides. “Is my subconscious really this dull??”

Rosalind Chast was born in Flatbush in 1954, the only child of two Russian Jews whose own anxieties included such things as operating toasters, unlocking doors, or throwing anything away. A New Yorker profile quotes a friend saying, “I’ve never seen anyone in life look as unhappy as Roz does in all of her childhood pictures.” Chast skipped a grade and left for college at sixteen. She eventually graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design, and returned, jobless, to live with her parents. At 23, she sold her first cartoon to the New Yorker. Titled “Little Things,” it featured a number of imaginary objects with near-English names like “enker” and “kellat” inside a then-scandalous hand-drawn box. The magazine paid her $250, enough, in 1978, for a month’s rent on a first apartment.

Even at a distance of half a century, “Little Things” is instantly recognizable as Chast’s work. Her sensibility formed early and has remained remarkably idiosyncratic and consistent. Her panels are hand-drawn, none-too-straightly. Her use of handwriting instead of type—another minor scandal at the New Yorker of the seventies—allows her, by varying font size and emphaticness of underline, to express far more than is possible with type’s mere bolding and italics. She has a limited closet of props, but she tends to use many at once. The result is a sort of crowded minimalism. Her characters are buck-toothed and stringy-haired and almost always viewed straight-on, arms flat against their side. The dad-mom-girl-boy families appear alone or together against circular rugs, lamps, and patterned wallpaper. They list awkwardly forward, as if about to fall out of the cartoon.

From the start, Chast showed a knack for an uncoolness so self-aware it became, somehow, cool. Early cartoons collected in Theories of Everything include a full-page spread that gives instructions for cocktails made only with different forms of water. A lost-looking man standing in front of the typical rug-lamp-wallpaper combo is titled “Never the Experiment, Always the Control.” A “Profile in Courage” features a hero who “[a]sked total stranger next to him in movie theater if he could possibly keep voice to a whisper.” Chast has said that she maintains an “idea box” in which she writes short phrases that occur to her, and it’s clear that many of her cartoons begin with their titles. Often the conceit is an enjambment of two idiomatic expressions: “Mental Baggage Claim,” “The Pill-of-the-Month Club,” “The Little Engine that Coulda Woulda Shoulda.”

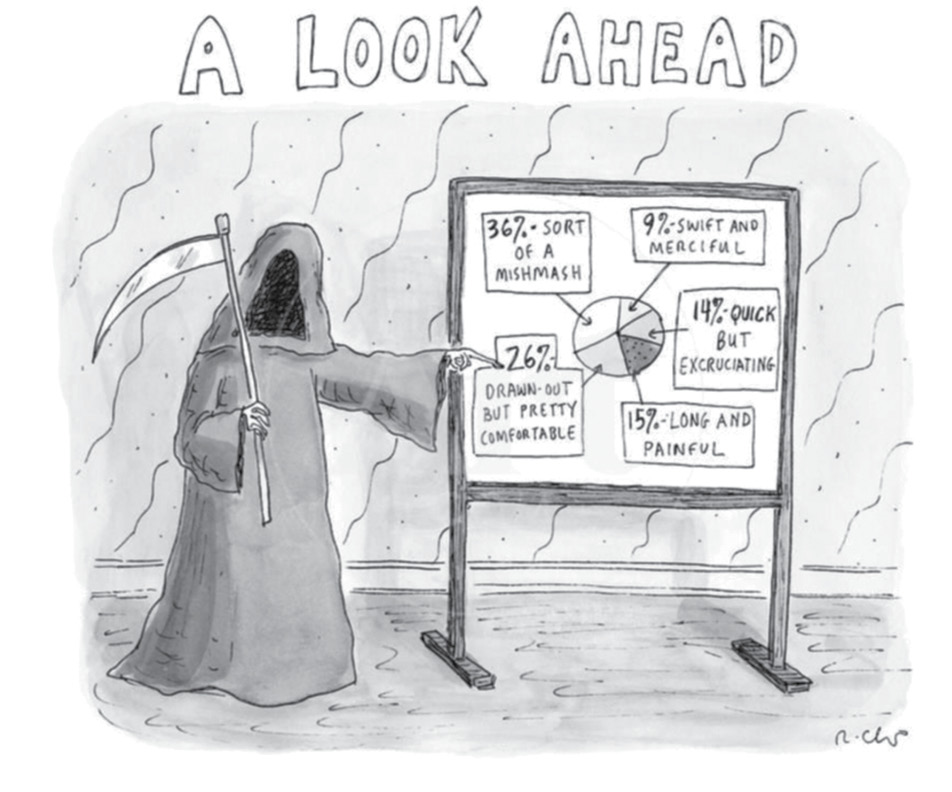

Part of the humor of Chast’s cartoons is visual, a divide between the anxious perfectionism of her characters, and the apparent shoddiness of their design, as if the cartoonist is herself too frazzled to draw a straight line. The other part of the humor is the discrepancy between the smallness of a character’s obsession or gaffe, and the bigness of their fear. Real panic in Chast-world is conveyed by upright hair and angled eyebrows and a face that grows bigger and bigger until it pokes out of the panel, often with hands to cheeks in a Munchian scream. “There are seven days in the week,” one cartoon declares. Beneath this, a terrified woman clutches her stomach and says: “What are we going to do???”

The New Yorker does not hire staff cartoonists, and Chast has long supplemented her freelance cartoon income with separate, often very short books. Beside collections of already published cartoons, these books tend to take one of two forms. The first is a compendium. Examples include the 2011 What I Hate: From A to Z (her most explicitly anxious book, which she dedicated to her parents) and the 2017 Going into Town: A Love Letter to New York, (which began as an informational booklet for Chast’s suburbia-softened kid). Chast’s instinct to taxonomize at length can deaden her humor, and these are generally not her best work. But her other longform mode is narrative, autobiographical, and generally spectacular. This form reached its apex in her staggeringly good 2014 memoir about her elderly parents’ slow deaths. Can’t We Talk about Something More Pleasant?, like Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home and Art Spiegelman’s Maus, manages to be very funny and very sad at the same time. It has a novelist’s grasp of psychology and pacing, and a magician’s sense of the visual gag.

I Must Be Dreaming, Chast’s latest book about “the surreal nighttime world inside her mind,” is, unfortunately, on the compendium side of things. Chast begins by explaining her passion for dreams: for the mind’s capacity to surprise itself. Then, in chapters organized by type, (“Recurring Dreams,” “Lucid Dreams,” “Celebrity Dreams,” “Nightmares,”) she describes many of her own, real-life dreams. Out walking, she comes across a beach in Midtown Manhattan, where she watches a documentary narrated by Chris Rock about nature and time. She looks in the mirror and discovers a third eye; it bothers her, but she can’t do anything about it, so she decides to forget about it.

I Must Be Dreaming is not dull: Chast has too unusual a mind and lively a pen to be actually boring. But in the absence of any narrative thread, it remains slight and random. Reading, I was reminded of the old maxim about short stories, how an ending should be surprising but inevitable. Here there is only surprise, surrealism for surrealism’s sake. It’s as if Freud, in his Interpretation of Dreams, merely listed some of his patient’s zanier visions and forgot to go on to the juicy revelations of the analysis. Chast seems aware of some of the difficulties of her chosen topic. Other people’s dreams, she acknowledges in her introduction, are often thought to be a drag. She suggests that this is because we find it so hard to understand dreamlands not our own. She quotes Heraclitus: “The awake share a common world, but the asleep turn aside into private worlds.”

For me, the real problem here is not separateness—we are in general quite interested in other people’s private worlds—but inscrutability. An unreadable dream is garbage, but a readable dream is gossip of the most soul-bearing and compelling kind. It’s worth comparing this book, in which Chast announces that she will omit dreams which are “too personal,” to a section of Can’t We Talk in which she describes the surreal world inside the mind of her dementia-addled mother. Elizabeth Chast, in her nineties, describes how her brother was born with a black person’s fingers, how Roz’s father died while she was pregnant with her, how her long-dead mother-in-law has put out a hit on her and can access her nursing home room via tunnel—none of which, of course, is true. As windows to an inner world, these are surprising but inevitable. There may be a version of the book in which Chast shares these types of dreams, but it’s not the version which was published.

Books by Roz Chast Discussed in This Essay:

Theories of Everything: Selected, Collected, and Health Inspected Cartoons 1978–2006. Bloomsbury, 2014, 408 pp.

Can’t We Talk about Something More Pleasant? Bloomsbury, 2014, 230 pp.

What I Hate: From A to Z. Bloomsbury, October 2011, 64 pp.

The Party, After You Left: Collected Cartoons 1995–2003.Bloomsbury, 2004, 104 pp.