Harsh prison sentences are often depicted as feminist triumphs. Harvey Weinstein’s sentencing was covered as a vindication of the survivors of his crimes, some of whom advocated the “maximum sentence” in interviews; an attorney statement celebrated Weinstein’s having to “live out the remainder of his miserable life behind bars.” After Bill Cosby’s sentencing, the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, an anti-sexual assault group, issued a statement of gratitude that “the court understood the seriousness of Cosby’s crime and sentenced him to prison.” Perhaps especially dramatic is the example with which Erica R. Meiners and Judith Levine open their book, The Feminist and the Sex Offender: the sentencing of Larry Nassar, the USA Gymnastics doctor who sexually assaulted hundreds of girls. Michigan Circuit Court Judge Rosemarie Aquilina gave the floor to 150 victims, allowing each to speak, after which she said of Nassar that if the Constitution did not forbid cruel and unusual punishment, she “might allow what he did to all of these beautiful souls—these young women in their childhood—I would allow someone or many people to do to him what he did to others.” It was a uniquely powerful act to let all those young women speak. At the same time, Judge Aquilina’s remarks invoke vengeance as a possible path toward justice and give tacit permission to those in prison with Nassar to rape or kill him. In fact, on July 9, 2023, Nassar was stabbed ten times in a Florida federal prison.

What should justice look like for victims harmed by violence? And what sort of justice is served by our prison system, in which close to two million people are currently incarcerated? It is no secret that the United States imprisons more of its population than any other nation in the world. We spend $80 billion annually on incarceration. There is a growing consensus across the political spectrum that prisons pose myriad threats not only to inmates, but also to staff and neighboring communities. It is increasingly clear that we cannot square feminism’s justice impulse with the horrors of the carceral state.

Gwenola Ricordeau’s compelling new book, Free Them All: A Feminist Call to Abolish the Prison System, builds a contemporary case for the intersections between feminism and prison abolition, dismantling the notion that the criminalization of violence against women benefits or protects women. Ricordeau argues that our penal system protects no one, is driven by profit, and disproportionately harms victims of violence, poor people, people of color, and LGBTQ people. Ricordeau, a professor of criminal justice at California State University, Chico, is originally from France and writes in French about the American justice system. Her tone is frank and substantive; she is careful with language, and the translation work of Emma Ramadan and Tom Roberge is precise and lucid throughout.

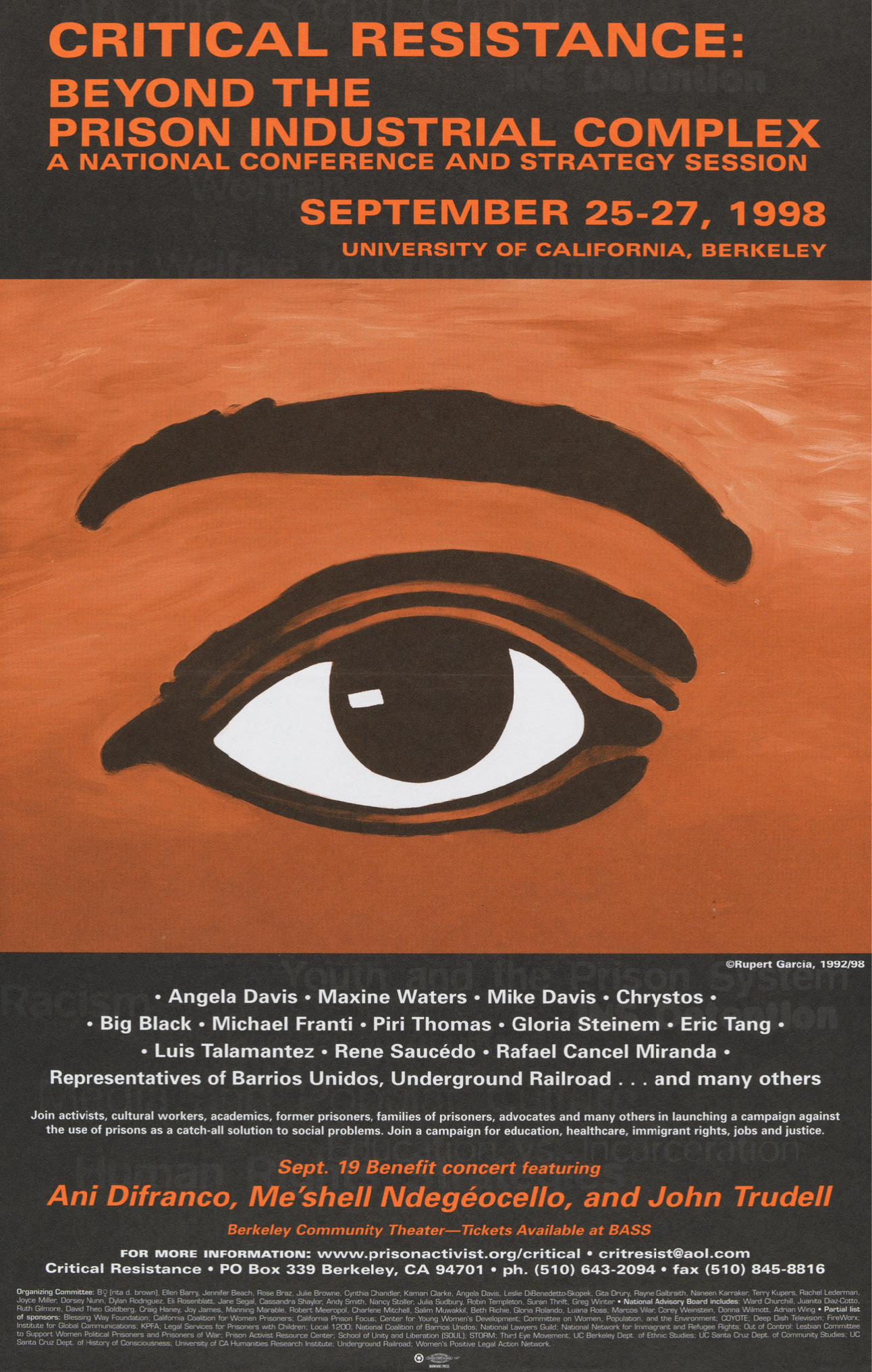

As part of a wide-ranging consideration of how we might move away from eye-for-an-eye logic, Free Them All contextualizes penal abolition in sometimes surprising ways. She avers that the abolitionist movement grew in certain ways out of the feminist one, which helped make connections between incarceration and other forms of coerced labor. For example, Angela Y. Davis, a central theorist of black feminism, authored Are Prisons Obsolete? in 2003 and helped found the abolitionist organization Critical Resistance. Davis led the school of thought that links American penal abolitionism to the slavery abolition movement of the nineteenth century. As Ricordeau writes, “The word ‘abolitionism’ and its relationship to the fight for the abolition of slavery is also echoed by certain currents of feminism” which have fought either to “abolish” sex work as a form of “modern slavery,” or else to “abolish regulations around sex work and thus abolish the means of controlling sex workers.” Feminism and abolition share a focus on domestic work, sexual harm and violence, and sovereignty over our bodies. Yet the tricky landscape of abortion and sexual harm serves as an example of both opposition and overlap: “feminism, by demanding the decriminalization of one and the criminalization of the other, has also shown that any critique of the criminal justice system must take power relations based on gender into account.”

But even as some strands of feminism have provided theoretical tools for dismantling the prison system, others have contributed to the rise of mass incarceration. Ricordeau is fiercely critical of the latter, which abolitionist feminists have dubbed “carceral feminism.” Since the 1970s, mainstream feminism, like the US justice system itself, has increasingly normalized mass incarceration. In the latter part of the second wave, “carceral” feminists, many of them civil rights lawyers and victim’s advocates, began to call for harsher punishments for sexual and domestic violence. This push was successful; longer sentences have become routine since the 1980s. Ricordeau acknowledges second-wave feminist abolitionist Karlene Faith’s recognition that resistance to the very concept of criminality is “a feminist imperative.” Many radical feminists agreed, yet Faith’s became a minority view, and the issue continues to reveal rifts within feminism. In the last decades of the twentieth century, the creation of “new categories of crime (such as incest or femicide); the reduction or the elimination of the prescriptive period (for offenses of a sexual nature); harsher sentences; and various innovations that aim to systematize indictments and prosecutions” have often been touted as feminist victories.

The fact is that mass incarceration does not make women safer. A significant number of victims never report violence because they know the system will ultimately not protect them. Moreover, the penal system specifically harms women. The United States incarcerates women at eight times the rate of China, and more than twice that of Russia. Activist Beth E. Richie’s work has shown that mandatory arrest policies for acts of domestic violence, for example, have “led to the arrest of more women and queer people, especially those who are racialized and poor, even when they were the same people who reported the violence.” San Francisco police kept a database of DNA samples from rape victims, using women’s DNA, without their knowledge or consent, to identify and in some cases arrest them as possible suspects in other crimes. Even where prisons acknowledge or try to address the particular damage done to women inmates, the system infantilizes them: “the prevalence of psychoactive drugs in prisons for women (much higher than in prisons for men) demonstrates the high level of attention paid to their behavior during their treatment—or, in other words, their domestication.” And although women’s prisons have historically had a reputation for being less strict, Ricordeau cites the work of scholar Meda Chesney-Lind to demonstrate that, since the 1990s, a “vengeful equity” in the US penal system has led to “increasing alignment of the rules of prisons for women with those of prisons for men.”

The abolitionist Nils Christie posits in his 1977 article “Conflicts as Property” that the penal system “steals” conflicts from individuals, disempowering communities from changing the circumstances which lead to conflicts in the first place. Feminist literature suggests that women are similarly disempowered, especially in controlling their own bodies, by all kinds of systems: domestic, legal, medical. Ricordeau deftly explores the intersections between these different forms of social and bodily control, using prisoner-activist Marilyn Buck’s analogy between the control of women’s private lives in prison and the control of women’s private lives by domestic abusers. Ricordeau’s research reveals that strip searches and the control of prisoners’ sexuality have a more profound psychological impact on female prisoners than male. Furthermore, prison environments normalize abuse. According to a bipartisan Senate committee report from 2022, Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) employees have sexually abused women in two-thirds of their women’s facilities, sometimes for months or years. Recently, the Los Angeles Times published a short video compiled from a flash drive sneaked out of a prison: among the clips was one of a woman, shackled to a wheelchair, only partially conscious and completely unattended, giving birth in the hallway of a prison. Her baby slips out onto the floor and lies there in a pool of blood.

Women, not to mention their children, are actively harmed by the prison system. And yet, despite all this evidence, even abolitionists rarely discuss the specific impact of mass incarceration on women. Ricordeau asks, “How many times have feminist organizations protested in front of prisons for women? Who is organizing protests for incarcerated women? What material and political solidarities exist among women who have relatives in prison?”

Personal anecdotes here are spare, but Ricordeau herself has family members in prison. Her feminism was born out of her abolitionism, which is far from abstract. Her heart, she writes, is in prison with “all these women. Those whose fate was sealed by the streets, the drugs, the prostitution, the running away. Those whose fate was sealed because they were born without the right papers, the right name, the right skin color.”

For Ricordeau, a feminist-abolitionist future would require making prisons, to use Davis’s term, “obsolete,” employing instead systems of community accountability, as well as political and structural changes to the conditions that allow harm and violence to take place. The co-founder of Critical Resistance, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, argues “abolition requires that we change one thing: everything.” This definition suggests that abolition is not an act of deletion or erasure, but one of “world-building.”

That vision, like the notion of prison abolition itself, can be misconstrued as excessively radical. Yet a close reading of Ricordeau and the massive cast of scholars, activists, and thinkers she cites, makes it clear that abolition feminism is in fact sensible and practical. In the section “The Women at the Prison Gates,” Ricordeau acknowledges the concrete work of women with incarcerated loved ones, which often goes unnoticed: “Being there, each week, at the gates. Sending money every month. Sending care packages when allowed. Lugging bags of laundry over and over.” All these are small acts of resistance. Free Them All is a call to participate collectively in that resistance. When Ricordeau quotes poet Audre Lorde’s famous lines “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” she notes how curious it is that this idea is so infrequently applied to the judicial system. Let’s apply it.