IN 2003, I WAS the only twelve-year-old in northern Illinois bedroom-dancing to Little Plastic Castle. I would put money on that. That album, released in 1998 and re-released this summer in its 25th anniversary edition, was perhaps the peak of Ani’s DiFranco’s mainstream fame. The song “Glass House” was nominated for a Grammy (ironic, given the song’s conceit: “trapped in my glass house / a crowd has been gathering outside since dawn”). Still, in 2003, none of my peers knew the name Ani DiFranco. They were listening to Dashboard Confessional and Evanescence, early and Christian-tinged emo, calculated perhaps to attract the attention of girls I knew back then, girls who, seemingly without cognitive dissonance, split their time between the mall and the megachurch.

I lived in a subdivision surrounded by cornfields on the opposite side of town from the mall, which was a place my mother refused to drive me. We were the countercultural type of evangelical. I was homeschooled until third grade. Any sophistication I possess I owe to my sister, who is thirteen years older than I am. When I was twelve, she was living at home for a few months between quitting her job at Congressional Quarterly and joining the Peace Corps. While she waited tables at night, I ransacked her CD collection. That was how I learned about Ani DiFranco. Also the Indigo Girls, Tori Amos, Dar Williams, really anybody you’d expect to find among the CDs of someone who’d spent the mid-nineties in a liberal arts dorm decorated with posters that said things like A woman without a man is like a fish without a bicycle.

The poster is not a rhetorical flourish: when I was six I spent a weekend in my sister’s dorm, and I can still picture the illustrated fish happily seated on an old-timey bike. It was unsettling. Did the fish want to ride the bicycle or not?

In the upbeat opening track of Little Plastic Castle, Ani sings:

People talk about my image

like I come in two dimensions

like lipstick is a sign of my

declining mind

like what I happen to be wearing

the day that someone takes

a picture

is my new statement for all of womankind.

When I was twelve, I didn’t know that there were enough generations of feminists for there to be conflict between them. I didn’t know that Ani, much like the dude who would become my other teenage hero, Bob Dylan, had pissed people off by deviating from the straightforwardly political folksongs of her early career.

In the year that I was born, 1990, Ani started her own label, Righteous Babe Records, at nineteen years old, carving out a place to make her “subcorporate” art. This included lovely acoustic songs about lesbian affairs and grittier ones about abortion and assault. Her anticapitalist, antiwar, anti-prison lyrics could take the form of spoken-word poetry or vocals ranging winsome to guttural over elaborate guitar plucks and esoteric tunings. The fear of men—their sexual and economic power—is a major theme of her early work: “maybe it’s because I’m hungry / and like a baby I’m dependent on them / to feed me.” She wrote these songs when she was still a teenager, and it shows in their earnestness but also in the naivete of someone who believes herself no longer naive. Ani had earned that stance, living in New York as an emancipated minor, full of precocious wisdom: “After nineteen times around I have found / they will stop at nothing once they know what you are worth.”

By the time Ani released Little Plastic Castle eight years later, she’d put out twelve records of increasing musical and emotional complexity on Righteous Babe. She was twenty-seven years old and occasionally appeared on MTV. Her cover of “Wishin’ and Hopin’” had just been used in My Best Friend’s Wedding. Fans were accusing her of selling out, and she was, scandalously, writing love songs about men. That same year, 1998, she married a man she would divorce five years later, and from her 1996 album Dilate, it was clear she was drunk on the kind of desire that warped her reality, her self-assuredness. Dilate is a labyrinth where the songs dance circles around themselves, accumulating gauzy layers of guitar plucks, vocal ululations, organ, and found sounds. “When I say you sucked my brain out / the English translation / is I am in love with you / and it is no fun,” she yell-sings on the title track which is, as far as I’m concerned, a contender for best breakup song of all time.

“This new little album I put out . . . [in] this kind of tortured melodramatic sort of vein,” Ani said on a track in Living in Clip (1997), the live album that followed Dilate. “All the righteous babes . . . just a couple of them got their little panties on a little too tight . . . because they’re now like, oh, you fuckin’ wench, just writing about, like, love and shit . . . and like . . . is this a conscious move away from overtly political songwriting? . . . like . . . no, man . . . I just got kind of distracted.” She dissolves into characteristically disarming giggles, and the crowd cheers.

On Little Plastic Castle, the politics are still there, as they would be for the rest of her ongoing career. They are mixed up with her own identity crisis. The titular plastic castle is a metaphor for homogenized corporate consumer culture, but also for Ani’s own dissociation, for the way love always makes us forget what we know.

They say goldfish have no memories

I guess their lives are much like mine

and the little plastic castle

is a surprise every time

and it’s hard to say if they’re happy

but they don’t seem much to mind.

And then she goes “yee-haw!” and the brass section waltzes in. There is exhaustion on this album, but also acceptance, even joy. “Let’s go, before I change my mind,” she tells her unreliable lover on “Gravel.” “Leave the luggage and all your lies behind.” She lets the language fail, the music take over, and this was where, when I was twelve, I skipped and tour-jetéed around my bedroom.

IT’S HARD TO say now what Ani did for me back then. What was it in me she touched before I had even been touched by a boy, or a girl? I don’t think I can recall the person I was twenty years ago clearly enough to figure it out, or maybe I’m not interested enough to reanimate that weirdly shaped Charis and all her obscure desires. There was something in the way Ani’s voice could warble between rage and sweetness in the same phrase (“Fuck you and your untouchable face”). There was something in how she helped me to historicize the neoliberal world I had inherited. “The old farm road’s a four-lane that leads to the mall / and our dreams are all guillotines waiting to fall” (“Subdivision”). Or “The left wing was broken long ago / by the slingshot of COINTELPRO / and now it’s so hard to have faith in anything” (“Your Next Bold Move”).

For the next six years, I listened to Ani constantly. I listened in secret, on my Walkman, on the school bus, in my bedroom, still dancing. I listened to every album I could get my hands on or torrent. And I listened all alone. Even when I began to know people who knew of Ani, none of them shared my admiration. They said that her voice was too mannered, that her songs all sounded the same. She was too angry or not angry enough. By this time, she had a baby with the man who would become her second husband. “I don’t want Ani to have babies,” said one of the two queer girls at my high school. “I just want her to have abortions.”

Even my sister stopped listening. She bequeathed me many of her CDs in 2004, when, after her Peace Corps stint ended in prolonged illness, she took off on an ill-fated cross-country romance with a man she had just met at a Howard Dean rally in Iowa (the one with the famous screaming). Later she moved to Europe and got married and listened only to Top-40 pop songs. (“Give me Ani or give me Britney,” I recall her saying once, explaining her intolerance for Alanis Morrissette.)

What a strange thing it must be to transcribe your whole life into folksong as you live it.

Listening now, I think I always vibed with the way Ani forced herself to get comfy with the dysphoria of self, of artmaking, of life on the road. “I learn every room long enough to make it to the door / and then I hear it click shut behind me” (“Dilate”). What a strange thing it must be to transcribe your whole life into folksong as you live it. “I’ve built my own empire out of car tires and chicken wire,” she sings on LPC, “I’m queen of my own compost heap, and I’m getting used to the smell.” She understood that we are alien to ourselves, and yet, she tried over and over to wrestle that amorphous alien into language, to both elude the pigeonholes and diffuse the misunderstandings, knowing all the while it is futile. “I am not an angry girl, but it seems I’ve got everyone fooled,” she sings on “Not a Pretty Girl.” It’s the theme of her late-nineties oeuvre. I’m not angry, I’m just doing my best. “I just write about what I should have done,” she puts it on “No Heroine. “I sing what I wish I could say / and I hope somewhere some woman hears my music / and it helps her

through her day.”

FOR MY TWENTY-SECOND birthday, a guy I dated bought me a single ticket to see Ani in Chicago, and I went alone.

No one I talk to ever brings her up in conversation. When I do, it’s with an air of apology, an acknowledgement of the uncoolness of my past taste. “I haven’t listened to her in years,” I say, which is generally true. Once in a while, I do listen, sometimes prompted by the odd cultural reference. The most recent was just a passing mention on the Netflix show Dead to Me, about two middle-aged women who (spoilers) accidentally kill each other’s husbands and become de facto life partners.

I should say no one I talk to ever brings her up other than Jennifer Baumgardner, who forced me to write this essay. I didn’t want to write it. It took me all summer, hours of staring at the computer and relistening to albums that left me feeling fourteen again. I threw 5,000 words away. What kept returning me to the task was the song “Joyful Girl,” from Dilate. “I do it for the joy it brings / ‘cause I’m a joyful girl,” Ani sings in the saddest, tiredest voice of her career. She sounds so close and so far away. The song’s subject was always a mystery to me. Now I realize it’s about what we would call, in the therapeutic lingo of 2023, “burnout.” How to keep doing the thing when it seems pointless, when the joy is gone. “Everything I do is judged / they mostly get it wrong, but oh well.” She consults her bathroom mirror, who asks, “Would you prefer the easy way? No? Well okay then, so don’t cry.”

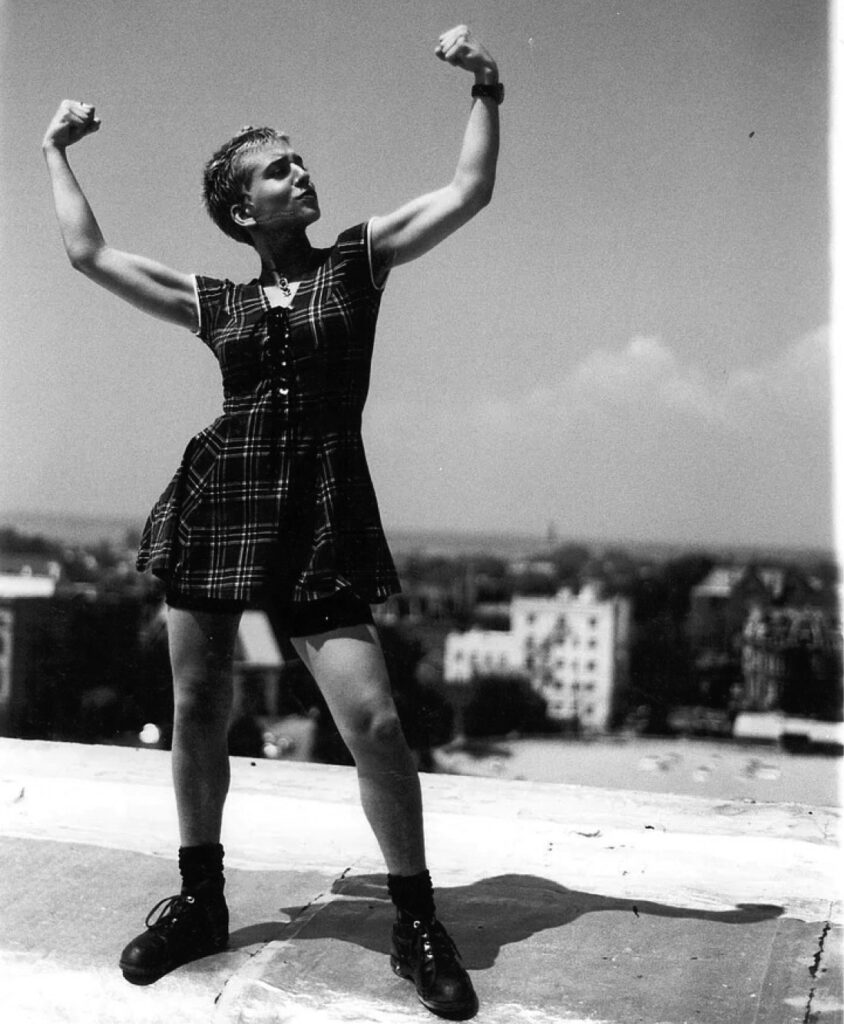

IN HIGH SCHOOL I shaved my head, mostly because I wanted to look as beautiful as Ani on the cover of her debut album. People did not seem to find it beautiful. Mostly I think they were confused by me. I was far less cool than the out lesbians with their fashion mullets, riot-grrrl tattoos, legible angers. I was bookish, and my closest friend once told me that she would have been popular if she had not been friends with me.

“No,” this friend said years later, when I told her how many times this comment had come up in therapy, “I meant that I would rather be friends with you, that your friendship meant more to me than being popular.” We are still best friends, and I get it. I came to resent Ani in the same way that my best friend resented me, in the way that we resent the people we recognize as kindred weirdos. The people who remind us popularity is nothing but a glass house.

There are Ani lyrics I loved back then that I now find so corny I can barely type them. One of my favorites at fourteen was “I am a work in progress / dressed in the fabric of a world unfolding.” I no longer feel that kind of optimism about the power of language to shape a self or a world. This summer I was so tired of my own thoughts I stopped writing them down at all. I tried to get my sister to write this essay for me. She declined but offered some input. “But make sure you preface this by saying we are drinking jalapeño martinis and borderline plotting my divorce,” she said:

Ani was a prophet. She anticipated so many things. Mass shootings, mass incarceration, MeToo. Everyone is bisexual now. In the nineties everyone just thought I was insane. She was the one person who made me feel like, maybe it’s normal to feel this angry. Maybe there’s a lot to be angry about. But she does it without pathologizing men, you know? Like in the song to her dad, she says, growing up it was just me and my mom against the world, but now I understand what all the fighting was about. Oh god, are you okay?

“Oh,” I said. “Yeah.” We were sitting on the patio of a trendy bar that opened in our hometown long after we had both moved away. July sun blazed off the river. I was wearing heart-shaped sunglasses. I had assumed my sister couldn’t see me crying.